Jilly Mehlman

Through a survey of Yale athletes and an analysis of team rosters, the News found that a disproportionate number of student-athletes are white and went to private high schools compared to Yale College’s overall population.

The difference was particularly stark for certain sports teams, including squash and crew.

“People get the misimpression that athletics is a diverse thing, or that it is often a way for people from lower income backgrounds to have an opportunity to get a college education,” said Rick Eckstein, a sociology professor at Villanova University who focuses on the commercialization of youth sports. “But we’re not seeing that on the ground, especially on ‘country club’ sports teams like squash or sailing or crew.”

According to an analysis by the News, approximately 770 Yale College students are on varsity sports teams. The News sent a survey to all student-athletes and found that more than 85 percent of the 86 respondents were recruited athletes. The group of respondents spans 29 of Yale’s 35 varsity sports teams.

Dean of Undergraduate Admissions and Financial Aid Jeremiah Quinlan told the News that, over the past five years, between 180 and 210 successful first-year applicants were “supported by a varsity coach” each year. Quinlan added that the number of supported students that Yale admits each year is lower than what the Ivy League allows and that Yale’s admitted student-athletes have a higher academic profile than the League-established standards.

In the Ivy League, athletic recruits generally must have grades and SAT scores proximate to those of admitted students overall. Coaches and admissions committees may recruit student-athletes who do not meet these standards, but only for exceptional athletes — and any exception must be balanced by admitting a recruit whose academic performance exceeds the standards, Inside Higher Ed reported in 2019.

“I am proud that in the ten years since I became Dean of Admissions Yale’s student body has become significantly more racially, ethnically and socioeconomically diverse,” Quinlan wrote in an email to the News. “At the same time, our varsity teams have been more competitive and successful than ever, winning Ivy League and national titles in a wide range of sports. I believe a student body that is diverse along multiple dimensions … contributes to better learning for students. Our student athletes contribute to all of these dimensions of diversity, and more.”

Comparing recruited athlete demographics with Yale College

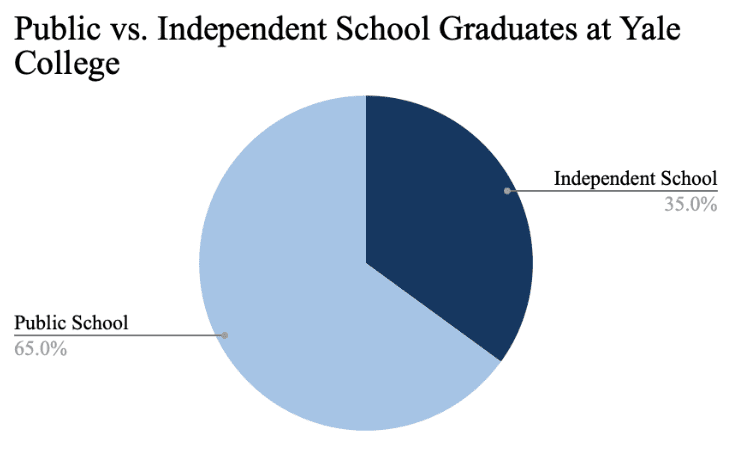

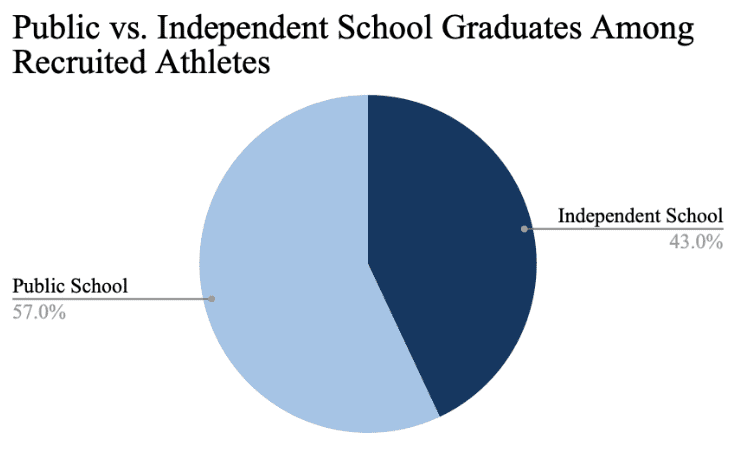

In 2022, 65 percent of first-year matriculants at Yale graduated from public high schools, while 35 percent graduated from independent schools, according to the Yale University Fact Sheet for the 2022-23 academic year. By contrast, a survey administered by the News found that 53.5 percent of athletes went to public schools and 46.5 percent went to independent schools.

Of the athletes who responded to the survey, 55.8 percent of athletes identified as white, compared to the 35.6 percent in the University as a whole.

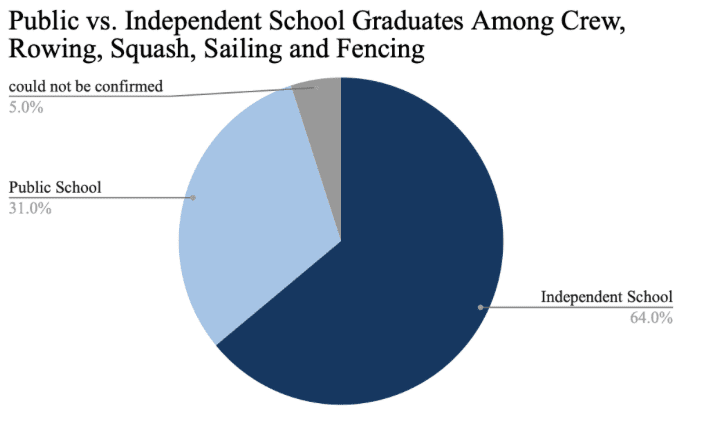

Through analysis of sports team rosters, the News was also able to determine demographics specifically among “country club” sports, as Eckstein described them.

Country club sports in the United States are expensive and exclusive to play — and often draw overwhelmingly white, wealthy and private school athletes, per Eckstein. They include sports like men’s and women’s squash and fencing, as well as women’s rowing, men’s heavyweight crew, men’s lightweight crew and sailing.

While Eckstein referred to country club sports as a phenomenon in the United States, the News’ analysis of all varsity Yale College athletes found that of the 221 students on so-called country club sports teams, at least 68 were international.

In addition to being less accessible to play in the United States, these sports are rare on the collegiate varsity level. Thirty-seven colleges have varsity squash teams, 156 colleges have varsity women’s rowing teams, 84 colleges offer men’s varsity rowing programs, 45 colleges have varsity fencing teams and 33 colleges have varsity sailing teams.

By comparison, there are 858 collegiate football teams.

According to the News’ analysis, at least 141 out of 221 athletes on the teams that Eckstein listed — men’s and women’s squash and fencing, as well as women’s rowing, men’s heavyweight crew, men’s lightweight crew and sailing — came from private schools, or roughly 64 percent. By contrast, about 31 percent came from public high schools. The News could not confirm the high school status of the remaining 11 athletes.

Eighty-five percent of athletes on the women’s squash team graduated from private schools; of the private school graduates, the average tuition of their high school was $52,158.

At least 86 percent of men’s squash players come from private schools, with the schools’ tuitions averaging to $59,753.

At least 71 percent of athletes on the men’s heavyweight crew team went to private high schools.

Out of 50 recruited athletes on the heavyweight crew team, three are athletes of color, as confirmed separately by two members of the team.

Expensive and “overwhelmingly white” rowing clubs

According to Thomas Allen ’25, a recruited coxswain on the men’s heavyweight crew team, white and wealthy overrepresentation in rowing is a result of the sport often being both financially and culturally inaccessible.

In high school, Allen rowed with a private rowing club based in his hometown of Marin, California. Membership on the club’s junior competitive team — the team open to high school students — costs $5,000 per year for students not receiving scholarships, according to the club’s website.

Allen described his high school rowing experience as “overwhelmingly white.” Outside of his rowing club, he said it was very uncommon for students to know anything about rowing. Allen himself learned about the sport from his older sister, who began rowing when he was in middle school.

“A lot of people had parents who had rowed or had been involved with the sport on a college level,” Allen said. “I mean, I can literally count on one hand kids who were not white. Every day, I would show up to practice and there would be multiple Teslas and G-Wagons in the parking lot.”

This dynamic was not reflective of his overall community, Allen said. He pointed to another high school rowing club near where he grew up in Oakland, California.

While the club is located in Oakland, which is home to many underserved communities and has a median household income of $85,628, Allen said that the club had few rowers who actually lived in Oakland. Rather, it drew almost exclusively from surrounding wealthy suburbs, such as Piedmont, which has a median household income of more than $250,000.

Unlike some other sports, Allen said that equipment costs are not particularly high for rowers, since equipment costs tend to be covered through club membership. To train on their own time, however, Allen said that some athletes purchase rowing machines for their homes, which tend to cost around $900.

“With rowing, the barrier is both cost-based and cultural,” Allen said. “You don’t have to pay for the equipment; my team readily gave out scholarships. But it’s more a matter of it being inaccessible because the communities in which good rowing clubs exist are all incredibly affluent and homogenous. It’s geographical and cultural. Most people just don’t even know the sport exists.”

He added that it is difficult to get recruited to row in college from smaller, less expensive clubs.

Allen said that in the spring, it was common for a college coach to be present at his high school club’s practices multiple times per week.

Every year, around five seniors from Allen’s rowing club would get recruited to top college teams. His senior year, two of his teammates were recruited to Columbia, one was recruited to Harvard and one was recruited to Princeton.

In the seven years before he graduated, the coxswains from his club were recruited to Yale, Brown, Princeton, Cornell, the U.S. Naval Academy and Northeastern University, Allen said.

The pay-to-play pipeline

According to Eckstein, recruited athletes are a relatively homogenous population even beyond “country club” sports teams, due to a phenomenon known as “pay to play,” where students who participate in club or travel teams, which often come at high prices, gain advantages in the college recruiting process.

These advantages often come through “showcase” events where private club teams compete with one another, attracting college coaches from top teams.

“The whole college recruitment system is rooted in these showcase tournaments and showcase regattas and showcase meets that are all tied to private club teams,” Eckstein said. “So if you want to get into these forums where college coaches are doing their recruitment, you’ve got to sign up with a club team or a travel team almost regardless of the sport. By focusing on these athletes, because it’s not a representative population, you’re more likely to get wealthier people.”

This pay-to-play process is likely responsible for the nearly 10-percent discrepancy the News found between public and private school student-athletes compared to the overall student body, Eckstein said.

It also contributes to deficits in other forms of diversity, such as geographic diversity, according to Eckstein.

He pointed to lacrosse, which he said is “pretty much unheard of” in urban and rural areas and is also rare in the Midwest.

According to the News’ roster analysis, 67 percent of athletes on the women’s lacrosse team and 64 percent of athletes on the men’s lacrosse team are from the Northeast. According to the University fact sheets for the classes of 2027, 2026, 2025 and 2024, between 29 and 31 percent of students in each Yale class are from the Northeast.

“By insisting on linking college recruitment to the pay to play pipelines, you’re all of a sudden weeding out huge swathes of the population who either can’t afford it or who can’t attend these tournaments that are sometimes thousands of miles away,” Eckstein told the News. “As long as that’s where the coaches are recruiting and the colleges are recruiting, those pipelines are just going to get stronger and stronger and keep weeding people out.”

Self-selecting

Even for sports that are not rooted in expensive club membership, the athletes that are recruited to play on the Ivy League level remain largely homogenous, according to an athlete on the track and field and cross country team. The athlete requested anonymity to “avoid any unexpected retaliation from Yale Athletics staff or the NCAA more broadly.”

She said that track recruiting is based solely on running time, rather than an athlete’s history of involvement with the sport or the status of their club or high school. To her knowledge, anyone who contacts a coach with interest and who has fast enough times can be considered.

However, she emphasized that this does not make the track recruiting process entirely democratic.

“There’s this argument that track is a sport that is open to everyone because all you need is a pair of sneakers,” she said. “But the reality is, most of the national-level competition was not available to me as a public school student. I didn’t get to go to a number of competitions because my school couldn’t fund that for me. They couldn’t afford to send me there. We were at the point where we won the state championship, but going to Nationals wasn’t even in the picture.”

While presence at national level meets may help athletes network with coaches at top colleges, it is not essential to be recruited, the student said.

But she added that there is a “certain type of person” who would know to reach out to an Ivy League coach with their times.

“You have to be empowered,” the student said. “You have to have some sort of insight into how to be recruited by an Ivy League school, of what will be required of you academically. I think for a lot of track athletes, running for the Ivy League seems unattainable. And also in some cases it can seem unrealistic, because the Ivies do not provide scholarships.”

The Ivy League is the only Division I conference that does not offer athletic scholarships — which a March lawsuit alleged to be a violation of antitrust laws. The student said the lack of athletic aid available at Yale and other Ivy League schools makes the pool of recruited athletes a “self-selecting” one.

The student added that many of her teammates at Yale have parents who went to Ivy League schools and competed on Ivy League teams.

While her parents did not attend Ivy League schools, the student said that she learned a lot about the Ivy League recruitment process from her older brother, who is an athlete at Dartmouth. Specifically, the “generous” need-based financial aid her brother received at Dartmouth opened her and her family’s eyes to how affordable Ivy League schools can be.

Allen said that the potential of scholarship money was not a factor that his family considered when deciding where he would attend college.

The eight Ivy League schools all offer need-based financial awards — intended to meet the full demonstrated financial need of admitted students — but do not offer merit or athletic scholarships.

Quinlan defended Yale’s prohibition of athletic scholarships, saying that Ivy League athletes are the best example of student-first student-athletes.

“I also believe Yale’s ability to meet the full demonstrated financial need of all of our students, including varsity athletes – whether they continue playing with their team all four years or not – provides a much healthier environment for student-athletes than schools that offer scholarships contingent on athletic performance,” Quinlan wrote in an email to the News.

Eckstein believes that continuing to recruit athletes from country club sports can be a “back door” tactic for Ivy League schools to admit more students who can afford to pay near-full tuition.

Yale advertises a need-blind approach to admissions, in which admissions officers consider and decide on students’ applications without knowledge of their financial status. But along with 16 other universities, Yale’s purported need-blind model was challenged in a lawsuit filed last year. The schools — including six of the eight Ivies — are a part of the 568 Presidents Group, a consortium of elite schools who collaborate in constructing financial aid formulas.

The group was sued on the grounds that they breached section 568 of the 1994 Improving America’s Schools Act, which states that schools can only collaborate if all members of the group do not consider financial need in their admissions process. A complaint filed in February alleged that all 17 schools consider students’ financial need through indirect means like donor preference and by considering financial means in waitlist and transfer admissions.

“It’s a good gamble to take someone who’s played golf in high school, or even someone who played club soccer or lacrosse and make guesses about their economic background,” Eckstein told the News. “It’s a good bet, and kind of a way to game the system.”

The Ivy League conference was officially formed in 1954.