What do you call a six-wheeled unicycle? A sexcycle? Tonight is the first show of the all-new Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus—six years after they shut the whole thing down—and the unicycles keep getting taller and taller. Wesley Williams, the One-Wheel Wonder, breaks his own Guinness World Record for the second time by riding a 34-and-a-half-footer. Meanwhile, Stix the Drummer shouts “Let’s rock this place out!” and performs a drum solo and a guitar solo. A man brings out a cannon, which propels his daughter Skyler the Human Rocket across the arena at 65 mph.

This is the circus in 2023, and while giant unicycles and human cannonballs remind you of the circus you saw as a kid, there’s something, or somethings, missing: trumpeting elephants and hoop-jumping tigers (not to mention clowns). For most of its 146-year run, from 1871 to 2017, animals pretty much defined the circus, but their use became increasingly unpopular in recent years. When my high school’s physics class took a field trip to the circus over a decade ago, I stood outside the school with the newly-formed Animal Rights Club holding a picket sign. My fellow protesters and I—and a lot of other people—wanted an animal-free circus, but we didn’t think much about what that might look like. Now I’ve come to Bossier City, Louisiana on opening night to find out what defines the circus now.

A circus without animals might sound oxymoronic. Un-American, perhaps. Even unacceptable, to some. (When Ringling Bros. announced in 2016 it would no longer be using elephants, Donald Trump tweeted, “Ringling Brothers is phasing out their elephants. I, for one, will never go again. They probably used the animal rights stuff to reduce costs.”) But the circus used to be a lot of things it isn’t anymore.

It no longer takes place in a huge tent, for one thing. This is thanks to Irvin Feld, who bought Ringling Bros. in 1967 under his company Feld Entertainment, which still owns the circus. Feld had managed tours for Chubby Checker and Chuck Berry, booking them in sports arenas. He convinced Ringling to abandon canvas big tops, which the circus had been struggling financially to keep standing, in favor of air-conditioned arenas.

And before getting rid of animals, the circus eliminated the so-called human freak show. This came up when Attorney Katherine Meyer led a suit against Feld Entertainment in 2000, accusing it of violating the Endangered Species Act. The court ultimately rejected Meyers’s claim, but while working on the case she studied old circus programs and saw not only lions and tigers and bears but also, “you know, the bearded lady, the fat lady, the man with no legs.”

“There used to be other traditions that the circus followed that it doesn’t follow anymore,” she says.

So: There are no callous displays of human disabilities and differences, which once helped define the circus. No “big top” tents, which once helped define the circus. No animals, which once helped define the circus.

What, exactly, is this new circus? What is any circus, for that matter? And why do we go?

As showtime approaches, a cloud of confused anticipation hangs over the Brookshire Grocery Arena in Bossier City. (The arena seats 14,000, but the upper deck is closed for this show, and the crowd numbers around 4,000.) “I don’t know what’s going on,” declares a 7-year-old girl with rainbow ribbons flowing from her headband like pigtails. When I ask another first-time circus-goer, 10-year-old Bryson, what he is most excited to see, he says, “Anything.” His 15-year-old brother, Devon, expresses relief at the lack of clowns. A pink-shirted blonde girl wants to see “an elephant balance on a ball.”

The set looks as if Dr. Seuss had redesigned my grade-school playground. When you walk in, you see interconnecting ramps, slides, and platforms. A swing set swings high above. A seesaw sits poised to spring acrobats into the air. A bicycle hangs suspended from the ceiling, ready to ride across a tightrope. Big, holey boxes, like refrigerator-size cubes of Swiss cheese, sit awaiting the start of the show. It looks like a 64-pack of Crayolas has exploded all over everything.

The lights dim. The crowd hushes. And it gets loud.

“Welcome to the showwwwwww!” comes a booming voice.

Cast members, as they are now called—there are 75 in all, from 18 countries, culled from a massive international talent search—flood the arena floor from every direction. Music cranks through the air. They sing: “We’re new and we’re proud and we’re going to get loud!”

Quite suddenly, the circus is on.

Trapeze artists spend so much time with their feet above their heads that I wonder if I’m upside-down. The teeter-totter propels an acrobat onto the shoulders of a human tower, a person jumps rope while riding a four-wheeled unicycle (the wheels are stacked vertically), and a jumbo-size hula hoop wobbles improbably around a regular-size waist. Someone balances upside-down on someone else’s head. Acrobats run on a conjoined hamster-wheel contraption called the Double Wheel of Destiny.

I, an adult attending the circus alone, hear myself say in awe—out loud, multiple times—“Whoa.”

Gold-sparkling gymnasts mirror one another on floating rings, like twins or interlocked lovers, while the lead vocalist sings “Beautiful like diamonds in the sky.” Three men I’ll call the stooges wear magician outfits—one orange, one green, one purple—and perform clownlike antics (slapping, bonking, falling) while standing on a red-yellow-and-blue platform, completing the rainbow.

Children and adults of all ages definitely will have nightmares tonight about Bailey the robot dog, who dons a pink mohawk and matching pom-pom poodle tail and a face that resembles that of the Teletubbies’ vacuum cleaner. Bailey and slapsticker Nick Nack hold a dance-off, the winner of which is unclear. A ten-person dance troupe performs a fusion folk dance, and three people stacked atop one another skip rope. There are lots of interesting haircuts.

Just as I’m thinking that the show could use a few fire spinners, I feel the heat of flames on my face.

My history with the circus is long and complicated.

It began, strangely, when I was born. I only discovered this a few years ago, when I was sorting old stuff at my parents’ house and found a yellowed letter declaring me a Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Baby. The circus had mailed it to me as a newborn—it must have been a deal with the hospital to recruit new circus fans at the earliest opportunity.

I did go to the circus as a kid: My father, a traveling salesman for a building-materials company, got tickets in the company skybox. While the adults mingled, I ate mixed nuts and my brother and I stared down at the three rings below. I laughed at the clowns, cheered the human cannonball. And then the elephants. They bumbled into the arena, ears flapping, looking as if they’d walked out of the dinosaur age, seeming almost too big to walk at all. But they did walk, stomping and parading mightily. They waved their trunks, flaunted their headdresses, smiled big smiles.

My next circus trip, or lack thereof: My high-school boycott, by which time I had figured out that those elephants weren’t smiling after all.

But then: When Ringling announced its closure in 2017, largely over increasing outcry about its treatment of animals, I felt vindicated. But a pang of nostalgia hit me as I remembered the skybox trip, and the elephants. I needed a college research paper topic at the time, and Ringling’s closure was the perfect one. This seemed to require going to the circus. (Patronizing the circus seemed a moot point, as it was on its last run.)

This was solely for scholarly research, and yet I found myself full of excitement to be at the circus again—with my brother, who I had convinced to tag along. The program burst with a blue-and-red-lettered title—CIRCUS XTREME—above a photo of the iconic elephant. Vendors sold overpriced stuffed elephants and rainbow snow-cones in plastic elephantine cups. The elephant in the room was that there were no real elephants in the room; they had been retired the year prior.

Tigers were still in the circus, and during intermission a voice announced over the intercom (I strained to hear over the screaming girl behind me who had been kicking my seat) that Ringling was “dedicated to saving endangered species.” Tigers, it said, were in danger due to human-tiger conflict, and the circus was partnering with organizations to help tigers in their native habitats. We could help by raising money for conservation projects, learning about the animals at the library, and “spreading the word.” “Together,” the announcer proclaimed, “we can all help save these amazing animals.”

After intermission, the lights flicked on to illuminate sixteen Bengal tigers. Tabayara Maluenda, the tiger trainer, stood in the spotlight’s center, whip in hand. He urged us to take one last look at the cats—to savor the beauty of the lone white tiger. I took in its power and grace, its ferocity and magnificence, its strong muscles and soft fur. The creatures looked so out-of-place in the Dunkin’ Donuts Center in Providence, Rhode Island, that for a moment I felt as if we, the audience members, were the spectacle, a bunch of humans eating fluorescent-dyed frozen sugar treats from plastic cups, and the tigers had come to stare at us.

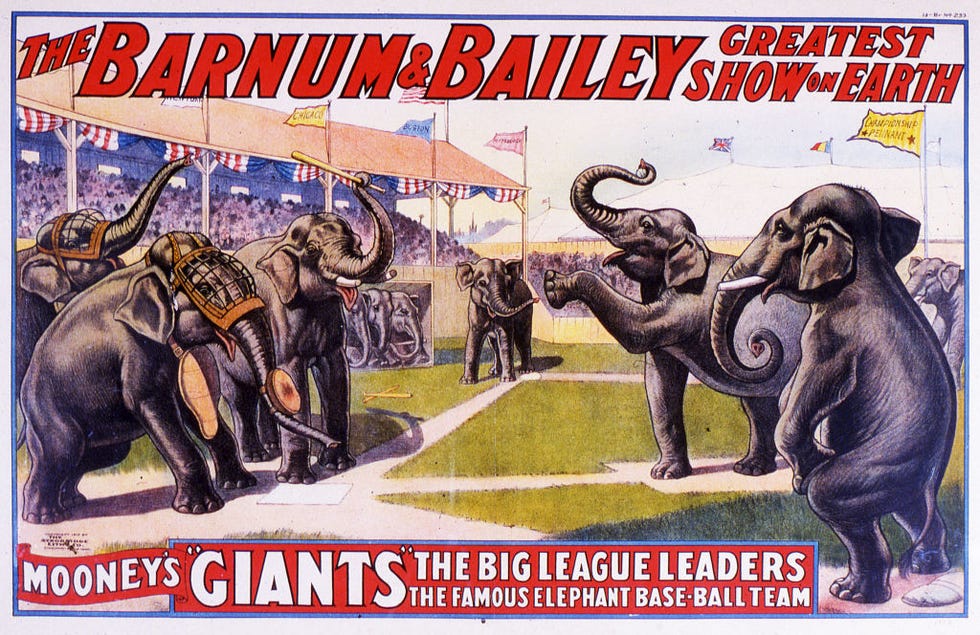

Assembling a humans-only circus for 2023 involved a long journey for both Ringling and the animal-advocacy movement. Some circuses have never used animals, from Cirque du Soleil to regional acts like Circus Smirkus. But elephants had forever been the star and symbol of the Greatest Show on Earth. “When entertaining the public,” P.T. Barnum once said, “it is best to have an elephant.”

As soon as America’s first elephant arrived in 1796, the huge creatures overshadowed all others in traveling menageries and circuses. If you don’t know about Jumbo, P.T. Barnum’s elephantine superstar from 1882 to 1885, you know some things named after him: jumbo jets, jumbo shrimp, jumbotrons, Jumbo supermarkets, Jumbo Jr. a.k.a. Dumbo, the Tufts Jumbos, the word jumbo, and Lyndon B. Johnson’s penis.

The iconic elephant that propelled Ringling’s long run of popularity also fueled its relatively rapid demise, set in motion by the 1975 publication of Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation and the birth of the modern animal-advocacy movement. Activists alleged all sorts of problems plaguing Ringling’s pachyderms: cross-country train rides in chains, beatings with bullhooks, severe foot problems from standing on hard surfaces, and outbreaks of herpes and tuberculosis. Animal-advocacy organizations and a former Ringling elephant-barn man filed the previously-mentioned 2000 Endangered Species Act suit against Feld Entertainment. In discovery, plaintiffs received what Meyer characterized as a “treasure trove” of materials showing the treatment of the elephants, including video footage and elephants’ medical records. (After a bench trial, the court ultimately dismissed plaintiffs’ claims for lack of standing to sue.)

Despite the end of the lawsuit, advocates circulated videos and documents online that they allege showed the poor treatment and conditions of circus elephants, and much of the public didn’t like it. Los Angeles and Oakland banned the use of the bullhook, the essential tool used to control elephants’ movements and guide them into and around arenas. With more city and statewide bullhook bans pending, the circus retired its elephants in 2016.

Ticket sales had been steadily declining for years. Meyer, the lawyer, says she saw dozens of emails from the public to Feld Entertainment saying they would stop going to the circus after finding out about the treatment of animals. For others, elephants were the main attraction, and they stopped going as soon as the elephants left the road. Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus held its final performance on May 21, 2017.

There are dozens of cool stories behind the new acts developed for the new circus. Here’s one of them:

A BMX bike, built for stunts and off-road racing, sat at the top of AJ Anaya’s Christmas list for years. His family had emigrated from Chihuahua, Mexico to Denver when he was five, leaving his bike behind. When his dad finally bought him a new bike for Christmas, it was a mountain bike (not what AJ wanted), which got stolen two weeks later. When AJ saw a professional BMX contest at age 14, he borrowed his cousin’s BMX bike and started going to the local skate park to figure out how to do a 360, then a backflip. When his cousin’s bike broke, the guys at the skate park put their old parts together to build AJ his very own BMX bike.

Now he gets paid to ride. BMX is already a non-traditional circus act, but Ringling Bros. casting director Giulio Scatola wanted to push the boundaries further. He asked Anaya to dream up something new for both the circus and the sport—preferably involving trampolines. Anaya wondered what it would be like to jump from a trampoline at the top of the ramp.

The BMX crew flew to Toronto to train with David Ross, the Canadian Olympic trampoline coach, who had never combined trampoline-jumping with bicycle-riding. None of the performers had either. They weren’t sure it was possible.

Turns out it was! In Bossier City, the bike sped up as Anaya went up the ramp, and time slowed down mid-air. “At one point everything just stops when you’re perfectly upside-down and gravity’s not pulling you, and you can almost stop and look over at someone,” he says. I like to imagine that he was looking at me, at me now but really at me as a child, a kid of the late 90s and early 2000s who dreamed of skateboarding but didn’t have a skateboard, who bought a cheap one at a yard sale with her brother, who took the board home only to find that the wheels were broken, whose dad threw the broken skateboard away, and who at age 23 dug that dream out of the trash and went to a skate shop and bought a new skateboard that is perfect in every way, and who now spends evenings getting pushed by the wind, and by her friends, along oceanside streets.

A pop! sounded deep in my eardrum as someone blew a tire and wiped out. A bike bunny-hopped down the staircase while Anaya and the gang bounced high on the trampoline into the air. They weren’t performing, really. They were the guys at the skate park. And there I was on the perimeter, watching enviously—as AJ had—like so many times before, now with the joy of knowing that I had my very own skateboard waiting for me at home, and that the world was now my playground.

Toward the end of the show, those three stooges produced an assortment of items from a toy chest of sorts and threw them into the air—bowling pins, flowers, a ukulele, a big fish—while Nick Nack tried to catch them and the One Wheel Wonder circled around on a unicycle that resembled a vertical accordion.

“I like the circus!” said the boy sitting in front of me as the stooges tripped and fell to the floor.

Animal activists will no longer be standing outside Ringling Bros. events with picket signs; some will be sitting inside the stadium with their families instead. “I was actually just looking at Ringling dates near me online yesterday,” Brittany Peet told me. She’s an attorney at the PETA Foundation, a supporting organization to People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). “I think I’m going to take my nephews to the circus. I never would have thought that would be something I was saying.”

If the circus can snap its fingers and turn an elephant into a BMX bike, if its components are so interchangeable, then we come back to that question: What is the circus? Maybe this thing that I have spent so much time researching is actually something extraordinarily simple.

I asked Juliette Feld Grossman, COO of Feld Entertainment, if the circus’s target audience has changed now that there are no animals in the show. “Our target audience is and has always been families,” she said. “It may sound a little bit silly in other contexts, but it’s always children of all ages. And just like [the shift from tents to arenas] was a major inflection point in the history of Ringling that probably couldn’t have been fathomed before that point, here we are at another inflection point where we reinvent so that this property can endure. And it endures because of what the audience takes away from it, which is not a perfect recalling of what acts they saw but rather the feelings they had. It’s that feeling of joy and excitement and wonder.”

What defines the circus is right in the name, circus: a circle or ring, in which something happens inside. Could be an elephant. Could be a bicycle bouncing on a trampoline, which no one thought was possible. In a few years it’ll be something no one thinks is possible today.

Grossman is right: A circus isn’t any one thing or act. A circus is made up of live acts that amaze and delight and astonish. And when we witness things that are amazing or delightful or astonishing, the world outside the ring, outside the tent, outside the arena—it melts away. Our problems aren’t problems, just for a little while. That is the great gift of the circus—that little while.

What I really remember from my trips to the circus isn’t the animals. I remember my brother: clinging to him as a kid, and laughing with him as an adult. You don’t need elephants to make a kid smile and an adult forget about the pile of laundry or the pile of bills, to forget about global pandemics and mass extinction and even animal abuse—to forget everything except the wind in her hair while she flies beside the ocean.

As the show ended, an operatic sendoff reverberated through the arena: May all of your days be Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey days!” Just a few years ago I would have recoiled at this, even taken it as a curse against me, a lifelong animal activist. But I was also a Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Baby, and now I smiled at the thought of it.

I never thought I would say this, but I like the circus.

Writer

Ashley Webster Babcock is a writer based in Portland, Maine, whose work focuses on the relationships between humans, animals, and our environments.