In her dreams at least, Phyu Nyo hoped to see all the colors of the outside world and experience freedom, even though she was in prison. But it never happened.

“I thought I could exist only in my dreams,” she said over the phone, recalling her 19 months locked up in two notorious junta prisons.

“But I never escaped from the prisons, even in my dreams. [The dreams] were all about prison, about running away and being recaptured. It was like my mind was also jailed,” the now 30-year-old said in a low voice.

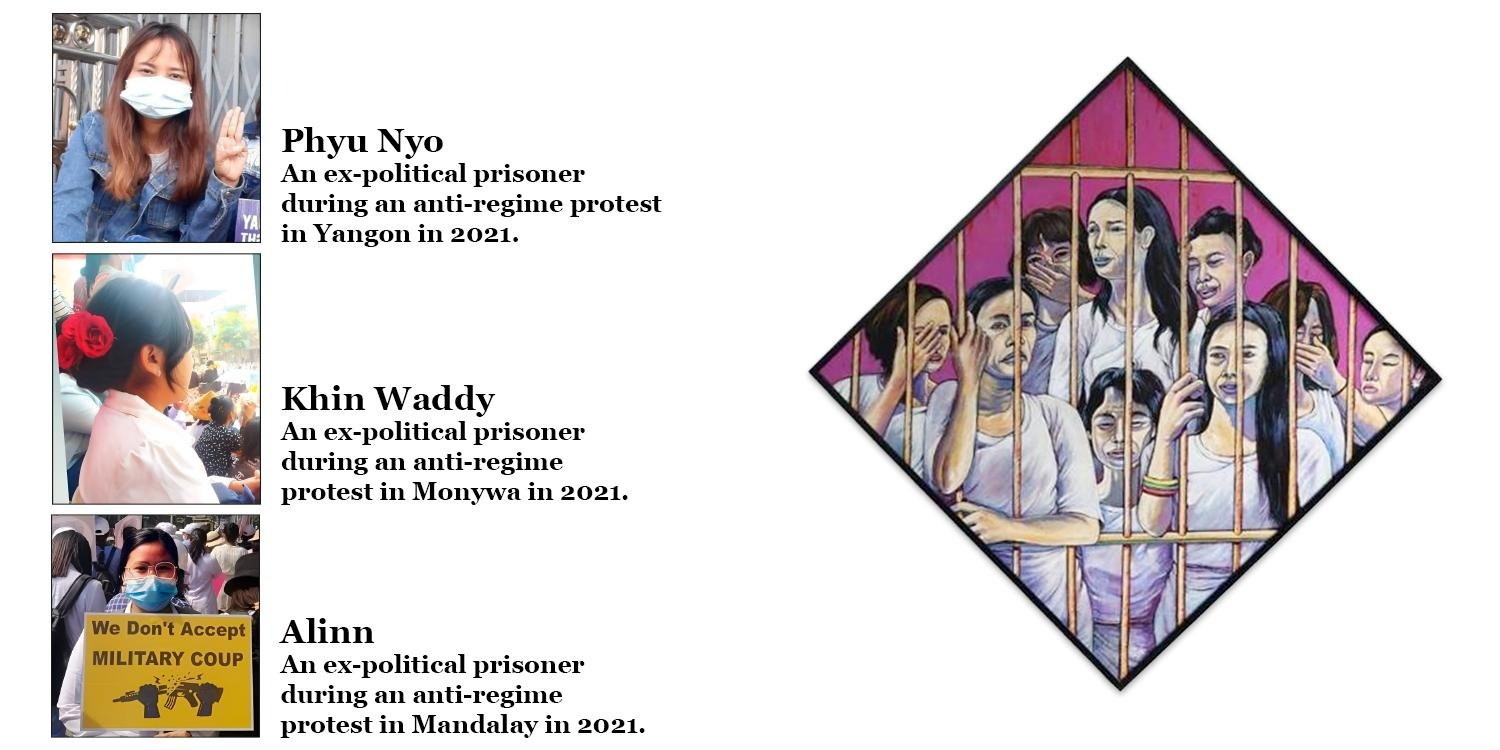

The number of female political prisoners in Myanmar is at a record high under the military junta led by coup leader Min Aung Hlaing. According to rights group the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), at least 4,883 women were arrested for anti-regime activities between Feb. 1, 2021 and Aug. 23 this year. Another 602 were killed, including 114 girls. Of those arrested, more than 3,770 are still in custody, 15 of whom face the death penalty.

The women arrested include political leaders, elected lawmakers, activists, striking civil servants, medics, resistance fighters, students, journalists, businesswomen and those from all walks of life.

Before the military staged a coup and overthrew Myanmar’s elected civilian government in February 2021, Phyu Nyo was a fashion designer and trainer from Yangon, living a decent life with her husband, who had a livestock farm and agribusiness.

But the pair were forced to become fugitives after participating in anti-coup protests and supporting striking civil servants who took part in the civil disobedience movement (CDM).

The two left their house in Yangon and fled to Mandalay to evade arrest, but were detained after being discovered in their hideout in the city in October 2021. The junta also sealed off Phyu Nyo’s fashion shop in Yangon and seized everything inside including clothes, bags and shoes.

She and her husband were sent to the junta’s notorious Mandalay Palace interrogation center, where Phyu Nyo was threatened with rape.

“They [the junta forces] yelled at me and said ‘We could rape and kill you!’” Phyu Nyo recalled.

Since the coup, women in Myanmar have been tortured, sexually harassed and threatened with rape in custody. The National Unity Government’s Ministry of Women, Youth and Children’s Affairs said in March that junta troops have sexually assaulted at least 122 women since the beginning of the coup.

Another form of sexual harassment that female political prisoners increasingly face is humiliating mass strip searches by prison staff.

Phyu Nyo said she had heard in June from female political inmates still held in Yangon’s Insein Prison that such searches had become worse this year.

Female inmates in Insein Prison are being forced to submit to thorough checks of their intimate body parts after court appearances. Told that it is necessary to ensure that the detainees don’t smuggle papers, female political prisoners are required to lift their breasts and expose their vulva. And prison staff wearing gloves touch and rub all of the inmates’ private parts and even use their hand to forcefully penetrate into the vagina during the searches.

In addition to the usual strip search humiliations, women who are menstruating are ordered to remove their sanitary pads in order to be strip-searched.

Supposedly done in order to search for smuggled “papers”, all such activities are violations not only of the detainees’ human rights but also their dignity, Phyu Nyo said.

Phyu Nyo was held in Mandalay’s Obo Prison and Myingyan Prison. During her imprisonment, she didn’t experience the most invasive searches into the vagina but did endure occasional body searches.

“Human rights abuses were common and the prison staff would swear at all of us, including women old enough to be their mothers and grandmothers, every day,” Phyu Nyo said, sobbing as she described the encounters.

“In prison you can’t do anything the way you wish, from speaking to taking a bath,” she said.

For bathing, prisoners are limited to 15 regular cups or 30 small cups of water a day.

Phyu Nyo said that while she would prefer not to think about those days in the military interrogation center and the prisons, as the memories are suffocating and painful, she felt a responsibility to speak up for her sisters who continue to languish in jails across the country, and to let others know their stories and what is happening behind bars.

“Sometimes, I have even thought of suicide. But the mindset that I will not give up on these guys, and that we will be free if we win, keeps me alive.”

Alinn, another former political prisoner who was also jailed in Obo Prison and Myingyan Prison for two years, similarly recalled that the prison authorities, especially in Obo Prison, treated political prisoners with hostility, adding that non-political inmates were encouraged to take part in abuses against political prisoners, and to monitor their activities.

A first year student at a nursing training school at the time of the coup, Alinn took part in peaceful protest rallies in Mandalay to demand the return of democracy in the country.

During a dawn protest on May 12, 2021 in Mandalay’s Pyigyidagon Township, she was violently arrested together with 30 other protesters. She was beaten on the head, back and arm, and collapsed during the arrest. Almost all of the detained protesters were later sentenced to two years’ imprisonment on incitement charges.

Alinn said many political prisoners suffer from health problems inside due to the lack of proper healthcare provisions.

“In prison, whatever your illness, they just give you para [paracetamol],” Alinn said.

According to accounts from media and rights groups, some political prisoners have died because of inadequate medical treatment and health care, including denial of emergency care at public hospitals.

The lack of adequate health care and medical treatment is only compounded by the growing number of female political prisoners that continue to be crammed into Myanmar’s overcrowded prisons across the country.

Khin Waddy, a 27-year-old former female political prisoner and student activist from Monywa, Sagaing Region, said she was forced to share a space, including while sleeping, with 100 to 150 inmates in one single dormitory in Monywa Prison. Around 60 percent of the inmates there were political prisoners, she said.

Being locked up with more than 100 people makes it difficult for prisoners to even change position from one side to another or turn around while sleeping, and inmates were forced to sleep face to face due to the lack of space.

Hygiene is another problem; those positioned near the septic tank were directly exposed to the smell, with liquid leaking from the tank passing near their heads.

To avoid being positioned near the septic tank, prisoners must pay the head of the dormitory for a sleeping space farther away, Khin Waddy said.

The former student activist and human rights advocate was arrested in May 2021 for providing support to 1,500 striking civil servants who joined the CDM following the military takeover.

Khin Waddy recalled that while she was being interrogated in the military interrogation center in Monywa, she was forced to kneel down while holding her hands up for 24 hours, and was beaten if she lowered her hands. She was also denied food and water. After two-and-a-half days of interrogation, she began experiencing stomach pains and vomiting and had to be sent to a military hospital.

While there she met Daw Khin Mawe Lwin, National League for Democracy (NLD) lawmaker for Sagaing Region’s Mingin Township, who was also hospitalized while undergoing military interrogation.

The 56-year-old was twice elected a lawmaker for her constituency, in both the 2015 and 2020 elections. The results of the latter were annulled by the military following the coup.

Khin Waddy said Daw Khin Mawe Lwin, despite her frail outer appearance, stood firm and served as a mother figure for all of the female detainees in the prison.

Later, Khin Waddy and Daw Khin Mawe Lwin were both transferred to Myingyan Prison.

In prison, the two engaged in activities together including political talks and discussions during which prisoners could exchange political views, and organizing strikes mirroring those taking place outside, such as silent strikes, Thanakha (traditional cosmetic paste) strikes and flower strikes, and strikes to mark occasions such as Martyrs’ Day, the anniversary of the 1988 uprising, and detained leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s birthday.

In prison, staging such activities can have repercussions ranging from the imposition of stricter rules or a reduction in the water allotted for showering, to a beating. There have been many reports of female political prisoners being brutally beaten and seriously injured, or being transferred to a remote prison, simply for asking that their rights be observed.

Khin Waddy was released in November last year. But instead of releasing Daw Khin Mawe Lwin, the junta hit the NLD lawmaker with another charge and transferred her to Kalay Prison.

Daw Khin Mawe Lwin suffered facial paralysis due to a stroke while in Monywa Prison. Denied timely medical care, she did not fully recover and later suffered another stroke in Kalay Prison, Khin Waddy said.

“If people like Amay [mother] Mawe were outside, they could do much more than us,” Khin Waddy said, adding that her wish is for Amay Mawe [Daw Khin Mawe Lwin] and all political prisoners to be released soon.

Despite the horrific, traumatizing experiences they have endured, female former political prisoners like Khin Waddy, Alinn and Phyu Nyo are not disheartened, and refuse to abandon their activism. Instead, they have joined other women who are at the forefront of the revolution.

Women from all walks of life have bravely participated in Myanmar’s democracy struggle under successive military regimes, including the current junta, to restore democracy in the country. Similarly, women civil servants in the education, health and other sectors have joined the CDM, refusing to work under military rule—to date, their strike continues. This is to say nothing of the many women resistance fighters who are fighting alongside their male comrades in the armed struggle against the junta.

Phyu Nyo, who was released together with her husband in May this year, said she has continued to dream of her days of imprisonment over the past three months.

“In my dreams, we are both still on the run and being caught, again and again,” she said with frustration. “Only when I wake up without seeing any [prison] bars, and recognize that I am now outside, do I feel relief,” she said.

However, Phyu Nyo hasn’t let her traumatizing experiences stop her from resuming her contributions to the political movement. She has joined the Political Prisoners Network-Myanmar, which was founded by her husband and other former detainees to help political prisoners still being detained by the junta.

Alinn, the former political prisoner from Mandalay, also joined the network with the same aim as Phyu Nyo.

“I couldn’t feel happy on the day of my release. Though I was free, people who had become like family members to me remained behind,” Alinn said.

Through the network, both Phyu Nyo and Alinn now help to send parcels containing medicines and cash to female political prisoners.

Khin Waddy is also working on raising funds for displaced people in Sagaing Region who were forced to flee their homes amid the junta’s raids and arson attacks.

“We want this revolution to end quickly. Only if we win will all the political prisoners be released, and thus we are determined to contribute in all ways we can. The same mindset we had while inside [prison], we now have on the outside,” Khin Waddy said.

Phyu Nyo said that some of the female political prisoners still locked up are serving terms as long as 30 to 40 years.

“I want all of them to escape quickly and return home. That can only happen if the revolution succeeds at the earliest possible time. And thus I will devote myself to the revolution,” she said.

With the exception of Daw Khin Mawe Lwin, the names of the women mentioned in this story were changed to protect their safety.