The U.S. House of Representatives was descending into uncharted depths of chaos, with one Republican even fretting that a debate over whether to oust Speaker Kevin McCarthy would devolve into a fistfight. But this was more important.

Laphonza Butler was more important.

On Tuesday afternoon, Rep. Steven Horsford, the Nevada Democrat in charge of the Congressional Black Caucus, slipped out into the hallway largely unnoticed. Then, beneath a statue of the civil rights shero Rosa Parks at the U.S. Capitol, he welcomed Butler into the caucus as California’s newest senator.

What caught my attention most were the photos of Rep. Barbara Lee of Oakland, who is running for the seat that Butler now occupies. Standing beside Horsford, she was smiling broadly and, at one point, balling her fists with the sort of excitement exuded after one’s favorite football team scores a touchdown.

Rep. Sydney Kamlager-Dove of Los Angeles was also there, beaming with pride.

Both Black women seemed to be genuinely overjoyed that Butler had just accomplished something they had long fought for: The representation of having a Black woman in the Senate. Butler is only the third. The second, Vice President Kamala Harris, had sworn her into the upper chamber moments before.

To look at these photos is to be reminded that some things are bigger than politics. That, even among ambitious people, not everything has to be a pitched and personal battle. And that maybe — just maybe — the old-fashioned collegial values practiced by Butler’s predecessor, the late Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who was mourned in San Francisco last week, aren’t all dead too.

But look at these photos long enough, as I have, and you’ll notice something else too: a hint of fragility in the California sisterhood of solidarity.

For decades, a few dozen Black women — supported by an influential network of lobbyists, activists, pastors and academics — have worked to get one another into elected office, often campaigning for each other, endorsing each other and fundraising for each other.

Karen Bass. London Breed. Kamala Harris. Shirley Weber. Maxine Waters. Holly Mitchell. Malia Cohen. Kamlager-Dove. Lee. And yes, Butler, plus many more. Not everyone gets along, but they’ve decided to work together anyway.

They do it not just for their own careers, but because they wholly believe in the notion that representation matters. That in a country as increasingly diverse as the United States — in terms of age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status and values — it takes an equally diverse group of leaders to understand it and govern it fairly and effectively.

And so, the sisterhood pulled together, coordinated with Black elected officials and activists from other states, and pushed hard for a Senate seat. First for Harris, and then, when a White-House-bound Joe Biden picked her as his running mate in 2020, for another Black woman just as qualified.

Together, they gave Gov. Gavin Newsom so much grief that he felt as though he needed to promise to appoint a Black woman if Sen. Dianne Feinstein were to step down before her term ended in 2025.

And when Feinstein unexpectedly died, they closed ranks and forced him to keep that promise — and to do so without any ridiculous preconditions about being a caretaker who would merely finish out the late senator’s term and not use the power of incumbency to run for election.

I should note that the governor now insists that his comment about wanting an “interim appointment,” made on NBC’s “Meet the Press” in early September, was misconstrued. Though that sure sounds like revisionist history.

Nevertheless, what the sisterhood — and the members of the Congressional Black Caucus who echoed their message — didn’t see coming was that Newsom would refuse to appoint the Black woman they wanted.

Instead of Lee, he elevated Butler.

“Everything that she’s been advocating for in the last few years meet this moment, as it relates to rights regressions, issues of civil rights, and issues of LGBTQ rights, women and girls, issues related to voting rights. She’s on the front end of all of these things,” the governor said of Butler. “This is a special person.”

Indeed, Butler, 44, is beloved. But so is Lee, 77. And so, Newsom’s decision has set off a roller coaster of conflicting emotions and silently shifting loyalties within the sisterhood and the broader network of lobbyists, activists and academics who support them.

“Every Black woman he called should have been like, ‘Do you need Barbara’s number?’” lamented one member of the sisterhood who, like so many, didn’t want to be named. “Nobody wants to be in a position where we’re bad-mouthing one Black woman about another Black woman. That doesn’t feel right to our values.”

Just consider this statement from Bass, who has endorsed Lee: “Laphonza Butler is an incredibly capable leader who I know will serve with distinction in the U.S. Senate on behalf of California. I first met Laphonza when she took the helm of SEIU Local 2015 and I watched as she worked to grow the union into the statewide force it is today. She has always been a fighter for the people and I look forward to working with her.”

Laphonza Butler’s unexpected appointment to the U.S. Senate has set off conflicting emotions and shifting loyalties among the sisterhood of Black women and their supporters.

(Stephanie Scarbrough / Associated Press)

And this from Lee on X, formerly known as Twitter: “I wish @LaphonzaB well and look forward to working closely with her to deliver for the Golden State. I am singularly focused on winning my campaign for Senate.”

Kimberly Ellis, director of San Francisco’s Department on the Status of Women, was more blunt.

She has known Butler for years, going back to their work together when Ellis led Emerge California, which trains women to run for elected office. They also belong to the same historically Black sorority, Delta Sigma Theta.

“I know she’s an incredible leader,” Ellis said, assuring me that she is happy for Butler’s appointment. “And that is separate and apart from the fact that all the Black women in California, in the political sphere, were in lockstep behind Barbara Lee.”

Until they aren’t. Because I’ve already heard a lot of confessions of, “I love and respect Barbara, but Laphonza …” And I suspect this is just the beginning.

Indeed, what was supposed to be a shared triumph with Newsom appointing a Black woman to the Senate has instead become a potential source of division. Butler is already testing the sisterhood.

::

Now I know what many of you are probably thinking: All of this sounds a little premature. And in many ways it absolutely is. Butler hasn’t even announced whether she’ll use the power of incumbency to run for a full term in 2024, or merely settle for serving the remainder of Feinstein’s for 15 months and step down.

“I have no idea. I genuinely don’t know,” she told my Times colleagues. “I want to be focused on honoring the legacy of Sen. Feinstein. I want to devote my time and energy to serving the people of California. And I want to carry her baton with the honor that it deserves and so I genuinely have no idea.”

If Butler decides to run — and I hope she does — she will have do so quickly.

The deadline is Oct. 13 for candidates to submit paperwork to request the endorsement of the California Democratic Party. She’d have to submit yet more paperwork by Nov. 15 to be included in the information guides about candidates that are sent to all registered voters in the state, and she’d have until Dec. 8 to officially join the March primary race, which is already well underway.

What will happen is anyone’s guess, but lots of people have opinions.

Former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa told my Times colleagues that “this race is too far along” and that Butler probably wouldn’t run.

“I do think she’ll do a very good job filling the shoes of a trailblazer,” he said.

Indeed, Butler is the first openly gay person of color to serve in the Senate. She also has a long and impressive resume, including more than a decade as president of Service Employees International Union Local 2015, the largest union in California.

She also was a UC regent, a board member of the national child advocacy organization the Children’s Defense Fund, a former director of the board of governors for the L.A. branch of the Federal Reserve System, and a senior advisor to Harris’ presidential campaign.

Most recently, she was president of Emily’s List, a national organization that helps elect Democratic women who support abortion rights.

For those reasons, Jeff Millman, who managed Feinstein’s 2018 Senate campaign, said that “Butler would be a very formidable candidate,” citing her ability to raise the vast sums necessary to run a high-profile, statewide race in California.

State Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D-Los Angeles), who has known Butler for years, mostly through their shared backgrounds in labor organizing, told me he’s surprised she even accepted the appointment because he thought she had zero interest in elected office. But that doesn’t mean she’ll be willing to give up the Senate seat once she’s got it.

“I will tell you, once you get elected,” he said, laughing, “it’s like crack cocaine.”

Then Jones-Sawyer grew serious. If Butler does run, it will be based on facts, not feelings. Alluding to her stint as a Democratic strategist, he described her as “a technical genius when it comes to looking at whether or not a campaign is viable.”

While Butler is figuring it all out, even the prospect of her entering the race has caused a recalculation of sorts in the sisterhood.

“All the Black women in California, in the political sphere, were in lockstep behind Barbara Lee,” above, says a longtime associate and admirer of Butler, speaking of the Senate race before Butler’s appointment.

(Michael Owen Baker / For The Times)

Part of this is because women, particularly Black women, often have a harder time getting elected to office and a harder time raising money because they have less access to high-end donors, which is one reason why organizations such as Emily’s List exist in the first place.

According to a recent poll by Pew Research Center, 53% of Americans believe there are too few women in high political offices in the United States, down from 59% who said the same in 2018. And yet, 65% of Americans think voters are far more likely to support a candidate if the candidate is a white man, rather than a woman of color.

There are a number of reasons for this, many of which are structural. Poll respondents cited gender discrimination, sexual harassment and women having to do more than men to prove themselves. Other reasons are rooted in racism.

Rightly or wrongly, this tends to breed a scarcity mentality. A fear that the more attention goes to Butler, the less will go to Lee. And Lee’s campaign needs the attention right now.

Under the top-two system, the two candidates with the most votes in the March primary will advance to the general election, regardless of party affiliation. And, according to the latest UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll, co-sponsored by The Times, at this point those two candidates would be Schiff, with the support of 20% of likely voters, followed by Rep. Katie Porter of Irvine, with 17%.

Lee is trailing with the backing of just 7% of likely voters.

For perspective, an identical percentage backs Steve Garvey, a Republican and former L.A. Dodger and San Diego Padre who hasn’t even announced whether he’s running yet.

Perhaps just as important, Schiff has raised nearly $30 million, Porter has topped $10 million and Lee has $1.4 million, according to federal campaign filings in July.

Ellis, a staunch Lee supporter, dismissed both the polling and the fundraising, as many other staunch Lee supporters from across the country have done.

“If the person that raised the most money were always the one who won,” she told me, “then Meg Whitman would have been governor of California.” And Rick Caruso would’ve been mayor of Los Angeles.

The hope among some is that Butler won’t seek election and instead will endorse Lee. As Boston Democratic Rep. Ayanna Pressley posted on X: “I look forward to your partnership & to having two incredible Black women serve consecutively when we elect @BarbaraLeeForCA as the next Senator from California.”

If Butler does decide to pursue a full term, another more likely scenario is that Lee will eventually drop out and then endorse her.

Or both Black women will run and let the voters decide in March. If that happens, I fear for the sisterhood. As one member told me: “I don’t think people will be quite as diplomatic as they’re being now.”

::

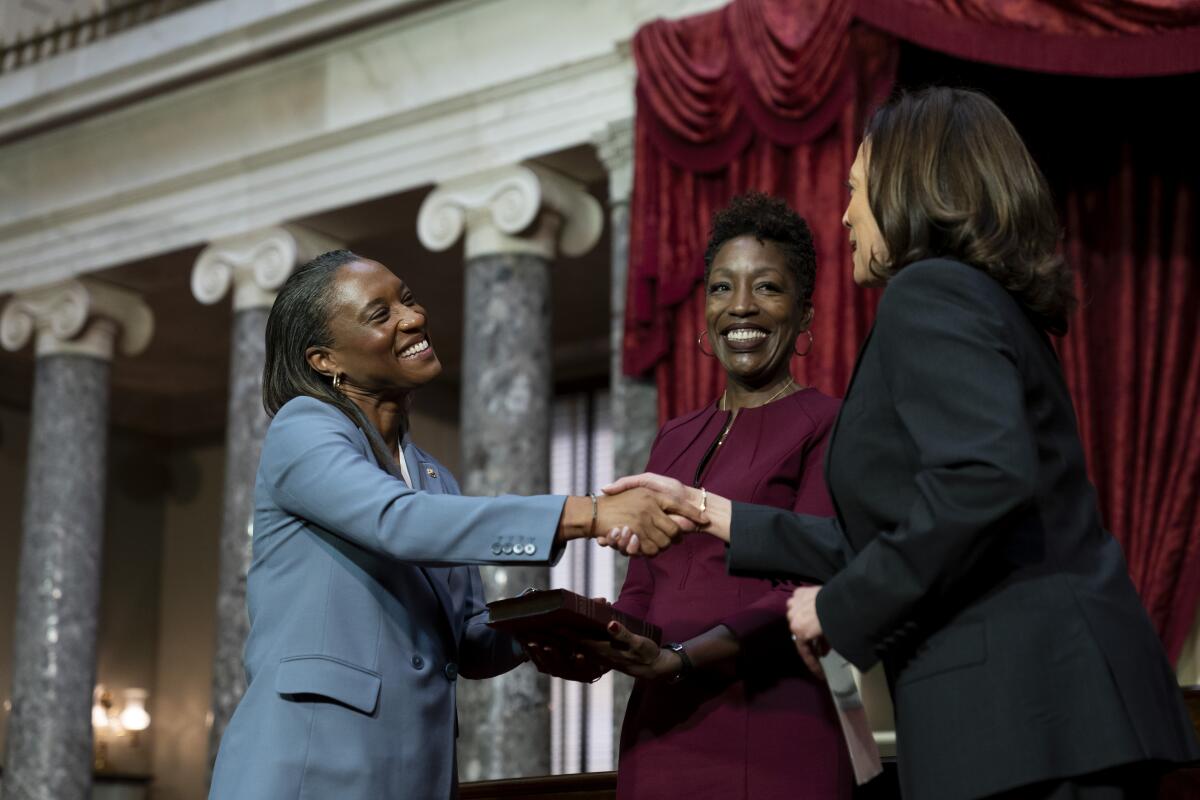

The appointment of Sen. Laphonza Butler, with Vice President Kamala Harris and Butler’s wife, Neneki Lee, raises new questions for the sisterhood about our aging leadership and waiting one’s turn.

(Stephanie Scarbrough / Associated Press)

When asked why she decided to accept the Senate appointment, Butler told my Times colleagues this:

“I can’t really be the leader of Emily’s List and encourage other women to do something courageous for their communities and for their country and I not be willing to do the same.”

Indeed, as a Black lesbian, it is courageous to step into such as visible role at a time when misogynistic forces on the far right are whipping up hate against women who want abortion rights, and against Black and LGBTQ+ communities for merely existing.

But there’s another type of courage at play here too, and that is the courage to challenge the order of things within the sisterhood.

Butler chose to take her turn when Newsom offered it, rather than wait her turn, as many Black women before her have long done and still expect others to do. And, by any stretch of the imagination, it is Lee’s turn. As a member of Congress for decades, consistently standing up for progressive causes and making tough decisions on foreign policy, she has paid her dues and would be an excellent senator.

But waiting one’s turn doesn’t hold the allure that it once did. Not when the reoccurring conversation in both the Democratic and Republican parties is over a rapidly aging leadership. Not when our next president is likely to be in his late 70s or early 80s. Not when Feinstein, the nation’s oldest senator at age 90, just died in office.

“Working until you die, that makes me sad,” said Dr. Flojaune Cofer, a public health advocate who is running for mayor of Sacramento. “I’m not taking away her agency to decide how she wants to live her life, but it denies the next generation of people to be able to call up your predecessor and say, ‘Hey, how did you handle this?’ All of our institutional memory goes away.”

Cofer is still all in for Lee, though, who would be 78 years old by the time she took office as California’s next senator.

Which is fine. But it’s all the more reason I’m glad Butler accepted the appointment. Her mere presence in the upper chamber will force a much-needed conversation about generational change in elected office that many just don’t want to have.

I just hope the sisterhood can handle it.

“This isn’t the first time that Black women have been put in this kind of a situation,” Ellis assured me. “We are oftentimes used for other people’s purposes and used against each other in that way, and — to your point — pitted against each other. But the reality is, that’s not how we roll. We refuse.”