By Season 5 of the prime-time soap opera Melrose Place, the character Alison Parker has been through a lot. Maybe not as much as Kimberly Shaw, who had multiple personalities and had committed at least one act of terrorism, but Alison, played by Courtney Thorne-Smith, was troubled enough that an entire section of her fan wiki page is simply labeled “traumas.” There was the time she was almost raped by an ex-boyfriend, who then shot himself. Or the time she recovered memories of being molested by her father right before she was set to get married to novelist–turned–advertising executive Billy Campbell (Andrew Shue).

But in Season 5, she’s dating dutiful bar owner Jake Hanson (Grant Show), who has cheekbones for days. Perhaps good times have come at last. Except they haven’t, of course. This is a soap opera, and no one can remain happy for long. It turns out that Alison is pregnant with Jake’s child and unsure if she wants to marry him. She and Jake split, and get back together. What will she do about this pregnancy?

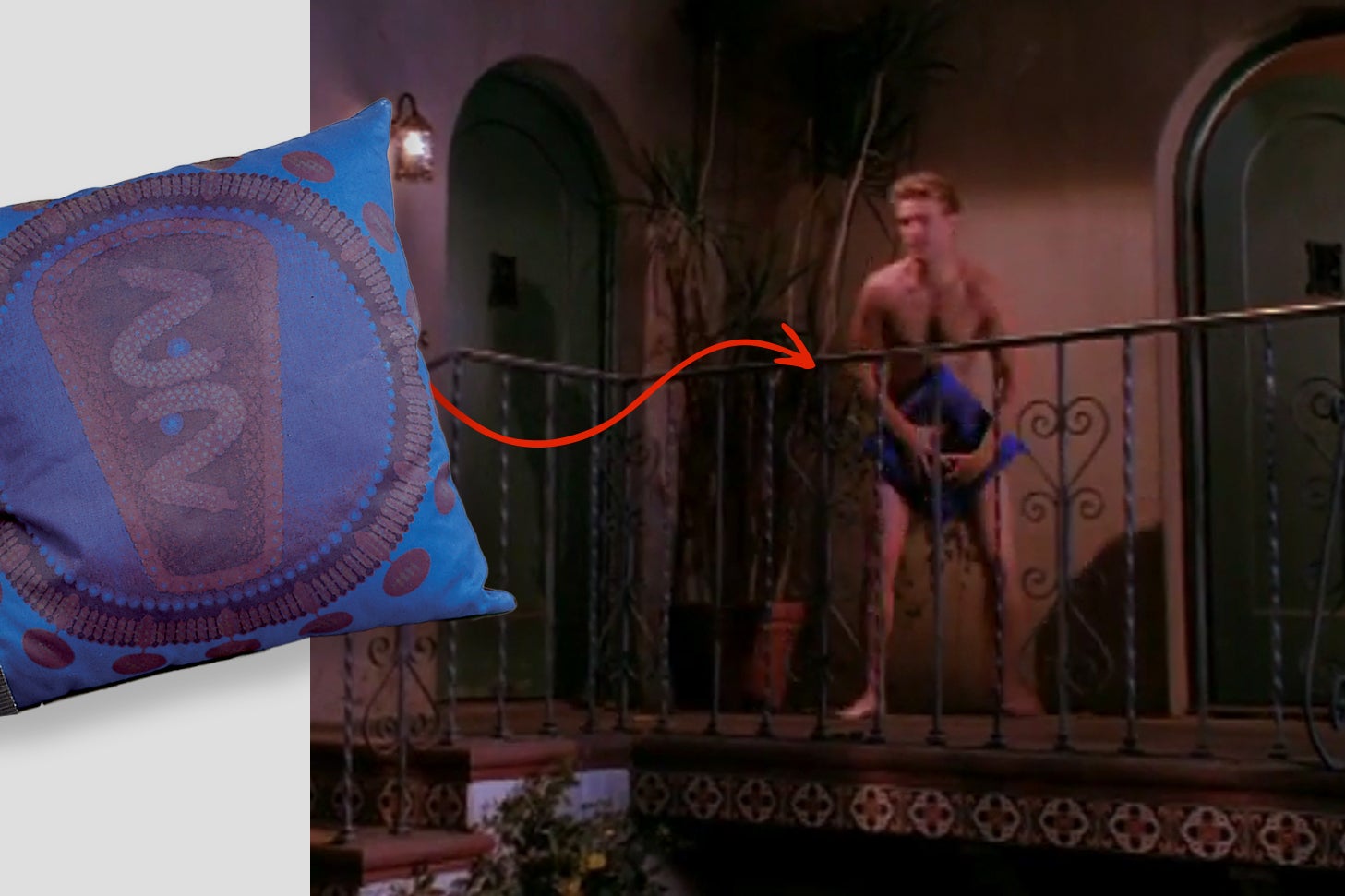

The answer, of course, is that she will have an extremely convenient miscarriage. This plot arc aired in the mid-1990s, when abortion wasn’t really an option for characters on television shows. If a series even openly discussed abortion, it risked the ire of highly organized media watchdogs on the religious right who would lead boycotts and threaten skittish advertisers. Yet if you look closely at “101 Damnations,” the Melrose Place episode in which Alison miscarries, you might notice something quite odd: There is a reference to abortion in the episode. It’s just visual instead of spoken. Through much of the episode, Alison Parker is draped in a quilt that bears the chemical structure of RU-486, the so-called abortion pill.

The GALA Committee/CBS Home Entertainment

And that’s not all. Watch enough episodes of Melrose Place and you’ll notice other very odd props and set design all over the show. A pool float in the shape of a sperm about to fertilize an egg. A golf trophy that appears to have testicles. Furniture designed to look like an endangered spotted owl.

It turns out all of these objects, and more than 100 others, were designed by an artist collective called the GALA Committee. For three years, as the denizens of the Melrose Place apartment complex loved, lost, and betrayed one another, the GALA Committee smuggled subversive leftist art onto the set, experimenting with the relationship between art, artist, and spectator. The collective hid its work in plain sight and operated in secrecy. Outside of a select few insiders, no one—including Aaron Spelling, Melrose’s legendary executive producer—knew what it was doing.

The project was called In the Name of the Place. It ended in 1997. Or, perhaps, since the episodes are streamable, it never ended. Twenty-five years later, discovering this project while researching a book about the culture wars of the late 20th century, I was left with several questions: Who were these people? Is what they made art? Did it matter? And how in the hell did they get away with it for so long?

Listen to another version of this story on Slate’s Decoder Ring.

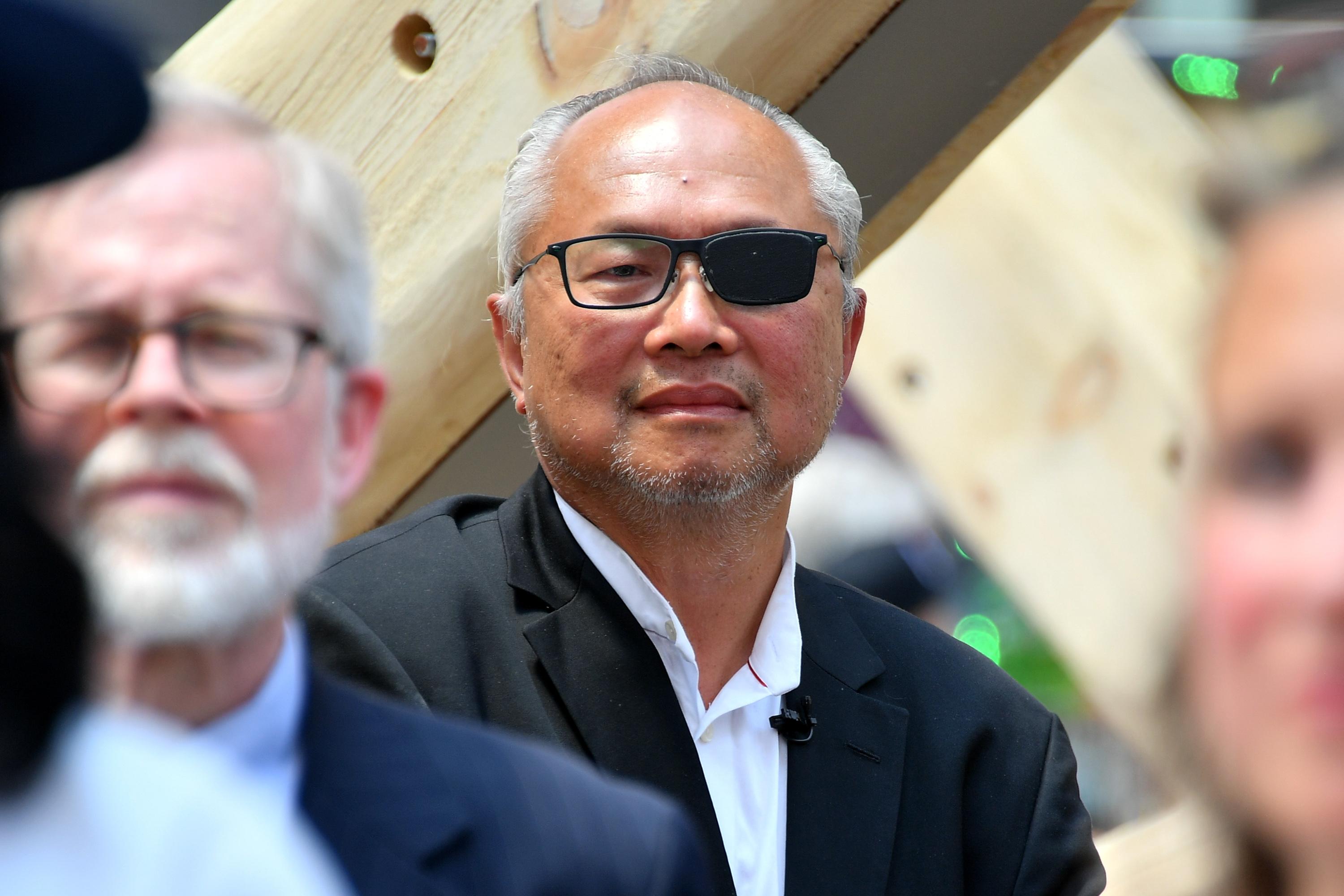

“Television,” Mel Chin told me, “is the modern cathode ray etching products into our brains.” Chin is the MacArthur “genius grant”–winning artist who was the mastermind behind the GALA Committee. On the phone from North Carolina, where he now lives and works, he explained the confluence of factors that led to him making secret art for a blockbuster prime-time soap opera.

In 1994 Chin was teaching at both the California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles and the University of Georgia, commuting thousands of miles through the air every week. One night, as he flew home to Georgia from L.A., he looked down at the vast landscape below him, “Kansas or some Midwestern state,” he recalled. But he couldn’t shake the place he had just left. “I started to think, L.A. is in the air. It’s through microwave transmission, through the television that’s on down there.”

He began considering an art exhibit that would exist not in a gallery but on TV, one that would use television’s power to etch ideas into viewers’ minds, instead of products. What would the rules of such a project be? How would you get the art onto the show? What television program would you use?

When he got home, his wife was watching TV, just like that person in Kansas or some other Midwestern state. Looming on the screen was “a huge, blond-haired head.” It was Heather Locklear, his wife told him. “I didn’t know who that was, but she moved her head and there was a painting behind her.” Then it hit him. “That’s it,” he thought. “It will be Melrose Place.”

To execute this idea, Chin had to pull off something like an art heist in reverse. Instead of stealing art from a well-guarded museum, Chin wanted to smuggle art onto the set of one of the most popular television shows in the world. In a heist, you also usually have a crew—a demolitions expert, an actor, a pickpocket, a money person, and so on. Chin didn’t have any of that. What he had instead were his students at Cal Arts and UGA.

Jon LaPointe, one of Chin’s students at Cal Arts, said he remembered thinking his new teacher was “a crazy son of a bitch.” Cal Arts was a conceptually minded school, so spitballing weird ideas was nothing new. “How would one, you know, insert art?” LaPointe recalled asking himself. “What would you make and what would you talk about? If you had access, what would you do?” They didn’t want to just mock up some paintings and put them on the set. That’s how art normally functioned in the TV and film world. A painting—usually a look-alike, since reproductions of real works are difficult and expensive to license—is nailed to a wall, where it becomes, in Chin’s formulation, “just a prop now.” Instead of making art that was merely a prop, they wanted to make props that were art.

Dia Dipasupil/.

Chin made it clear to his students that for this project, their professor was just part of the collective. Chin didn’t want to be a guru. “I had to subvert my hierarchy as this scholar and say, ‘I’m one of you,’ ” he recalled. “ ‘If you come up with a good idea and you don’t know how to fabricate it, because I do know how to fabricate things, I will make it.’ ”

Together, Chin and his students made the most critical decision: It had to be secret. No one could know they were the ones sneaking avant-garde art onto television—indeed, no viewer should be aware that any art project was happening at all. In this way, the project was very in tune with the leftist art world at the time. The 1990s was the decade of widespread “culture jamming,” an artistic response to the rise of global capitalism and free trade. Culture jamming was like hacking, but instead of using code to hack computers, culture jammers used pranksterism to hack and disrupt the reality imposed on us all by major corporations.

Absent an internet to use for viral fame, culture jammers used mass media—particularly the nightly news—to draw attention to the issues they cared about. One loosely organized group, which called itself the Barbie Liberation Organization, swapped the voice boxes of talking G.I. Joes and Barbies in 1993. Suddenly, toys across the nation weren’t conforming to gender stereotypes, and both parents and the nightly news took notice. In the Name of the Place wasn’t looking to punk Melrose viewers in quite the same way, but it tried to co-opt a work of mass media and turn it into a distribution network for radical ideas. The problem was: How?

Melrose Place was a massive hit, part of the insurgent Fox network’s youth-oriented, edgier programming that also included Married … With Children, The Simpsons, and Beverly Hills, 90210, the show from which Melrose had been spun off. Both 90210 and Melrose had been masterminded by Aaron Spelling, the god of the prime-time soaps, whose previous hits included The Love Boat and Dynasty. Due to its propensity for wild plot twists and the breakneck pace of its storytelling, Melrose was appointment viewing, the kind of show for which people held watch parties. Mel Chin’s wife wasn’t the only person tuning in to Melrose Place; about 14 million people watched the show every week in the fall of 1994.

One thing the show was not, however, was particularly political. The closest Melrose Place got to any kind of political statement was a character named Matt, who was openly gay—in theory. Matt almost never had boyfriends, barely had a personality, and existed largely to demonstrate the forward-thinking liberalism of the characters around him. Part of what made Melrose Place such a ripe target for Chin and his students was the gap between its surface-level political signaling and their die-hard leftist beliefs.

Watching Melrose one night, the crew noted the name of the set decorator in the credits: Deborah Siegel. Chin opened the Los Angeles phone book and, lo and behold, her number was listed. He called her.

“I ignored him,” recalled Deborah Siegel, who now goes by Deborah Siegel Cosentino, “as I do many people who call.” But Chin kept trying, and when the two finally spoke, she found herself intrigued. Here was interesting contemporary art, offered to her royalty-free. What’s more, as a “very leftist, activist person,” Cosentino “felt that Melrose Place was not in line with my beliefs.” Quickly after their phone call, she agreed to put the creators’ artworks onto the show.

“Oh, shit,” Jon LaPointe remembers thinking when he found out. “This just got a little weird. And real.” They had to move fast. Soon, their nonhierarchical collective had a name (the GALA Committee—the GA for Georgia, the LA for Los Angeles), project managers, grant funding to supplement the commissions, and a workflow. Chin went on a recruiting drive to find working artists to supplement the GALA Committee’s ranks. Constance Penley, an artist and media theorist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, remembered her call with Chin vividly: “A project where we would go inside the text, inside the modes of production, the means of production, to remake it from the inside out,” she said. Thirty seconds into the call, she said, “I get it. I’m in.”

Communicating via fax machine, the bicoastal organization would hash out ideas, then send final designs to be fabricated by a company called Grand Arts in Kansas City, Missouri. From there, they’d be shipped to Cal Arts and brought to Deborah Siegel at Melrose Place. Every Monday, members of the Georgia crew would gather at a local pizza parlor to watch the show as it aired and take notes on what worked and what didn’t. When they spotted pieces—often on the screen for the length of an eyeblink—they’d point them out. “It was hit or miss,” LaPointe said. “Actually, mostly, it was miss.”

The needs of a hit television show don’t exactly match the goals of a radical artists collective. Melrose Place’s episodes were made very quickly—sometimes multiple episodes were filmed simultaneously—and the props crew did not have time to wait around for a bunch of art punks to decide on a design. The artists also had no idea what was going on in the show from week to week. They simply designed provocative and fun objects, dropped them off, and hoped for the best.

Two pieces from this period stand out, however. The first is called Safety Sheets, a set of linens for the bedroom of playboy doctor Peter Burns (Jack Wagner) made by students in the textiles department at the University of Georgia. The sheets can be seen in multiple episodes of the show, but they’re especially noticeable in an episode called “Run, Billy, Run.” During this episode, Burns and his current lover wake up one morning in his apartment. If you know what you’re looking for, you can identify the pattern on his bedsheets and pillowcases: unrolled condoms. At the time, the Federal Communications Commission wouldn’t allow unrolled condoms to be shown on TV. LaPointe still remembers how he felt when he saw the camera linger on the couple in bed, the sheets clearly visible. “That was the moon landing,” he said. “Oh my God, it’s actually happening.”

The GALA Committee/CBS Home Entertainment

The other important piece was a work called Total Proof, a poster that nearly derailed the entire project—but ended up transforming the collective’s connection to the show. Several of the main characters on Melrose Place worked at an advertising firm called D&D, and the GALA Committee frequently made posters and other samples of D&D’s “work.” One of these was a parody of once-omnipresent Absolut Vodka ads. You may remember these: You’d open up your issue of Premiere, and there’d be an Absolut bottle with a halo on it and the slogan ABSOLUT PERFECTION. The GALA Committee’s version involved a vodka bottle superimposed over the wreckage of the Oklahoma City bombing, at that point the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil. TOTAL PROOF, the poster read. The bombing had happened less than a year earlier.

This piece was the culture-jamming GALA Committee at its culture-jammiest, an angry, funny piss take on capitalism’s rapacious ability to commodify anything. But a line producer on the Melrose Place set noticed the poster during shooting and found it in extremely bad taste. He brought it to his boss, executive producer Frank South. South called Siegel into his office and asked her to explain what was going on. When she told him about the GALA Committee, his response was not what anyone would’ve expected.

“I said, ‘Well, shoot!’ ” South told me recently, smiling. “I was really enthusiastic.” It turns out that prior to his work in television, Frank South was an artist in downtown New York, helping to run a gallery and performance space in TriBeCa. It was experimental performance art that had led him to writing plays—several of which were directed by Robert Altman—and then to television. Edgy, political art was nothing new to him, and after a meeting with Mel Chin, he decided not only to let the GALA Committee continue its work, but to fully involve it in the production process.

Now members of GALA Committee would receive scripts in advance and could craft specific pieces depending on the show’s needs. They would be allowed to come to set and consult on installations. They would be so fully integrated into the production process that the series’ design staff would be added to the list of committee members. As the relationship between the GALA Committee and the show deepened, In the Name of the Place became, in Chin’s words, “a collaboration. The intention was not to undermine the host, but to enhance its possibility for the transmission of ideas.”

South also made another decision: not to inform his boss, Aaron Spelling. “I always intended to tell Aaron about it,” he told me. “But at one point, I decided not to, because it was getting so integral” to the show’s process. “You know: Apologize, don’t ask permission.”

Over Melrose Place’s fourth and fifth seasons, the GALA Committee wound up smuggling more than 100 pieces of subversive art—VHS boxes marked STD, a baby’s crib mobile designed to look like an enormous remote control, a painting of “fireflies” based on the U.S. military’s bombing of Baghdad—onto American television screens. Some of the artworks were quite small—a cigar box that couldn’t be opened, for example, symbolically referencing the Cuban embargo—but some were massive. GALA went to the set of Shooters, the local watering hole frequented by the show’s characters, and relabeled all of its liquor bottles with works meant to document the intertwined histories of slavery, agribusiness, and alcohol in the United States. The committee designed an ad campaign for D&D called “Family Values,” which featured silhouettes of same-sex couples with children. (The “campaign” won the character of Billy a fictional advertising award.) Over those two and a half years, nearly every Melrose Place episode contained some large or small political statement, crafted by contemporary artists, tucked into shots with the show’s bombshells and hunks as they faked blindness, abruptly drowned, and tricked one another into thinking they had epilepsy.

The GALA Committee/CBS Home Entertainment

Food for Thought, one of GALA’s most audacious pieces, hid in the most mundane place: Chinese takeout bags. Envisioning Melrose Place’s future syndication around the world, Chin realized that GALA’s work “did not have to be limited to English. A billion people read Chinese.” One takeout bag sported the ideogram for human rights alongside the one for turmoil, the euphemistic term used by the government during the Tiananmen Square massacre. Another read “Stolen artifacts, national treasure,” a reference to colonial looting.

The GALA Committee even helped conceptualize a main character on Melrose Place, Samantha Reilly (Brooke Langton), a visual artist who joined the show in Season 4. Melrose flew in 15 GALA women to brainstorm the new character and to fabricate her brightly colored artwork, which referenced the sunny pools and California landscapes of David Hockney. But each painting contained a hidden darkness, the ghostly echo of the tragic histories of Los Angeles: Locations included 10050 Cielo Dr., the house made famous by the Manson murders; the house where Marilyn Monroe overdosed; and the Viper Room, where River Phoenix died.

The GALA Committee/CBS Home Entertainment

What first stands out when you look at these paintings today is their naïveté. They are rough-and-ready creations, made very quickly by a group of people on a deadline. They are missing the placid craftsmanship of the Hockneys on which they are based. But what they lack in mastery they make up for in playfulness, a spirit that contrasts starkly with the haunted quality of the spaces they depict. They’re like a palimpsest: There’s an image on the surface, and another underneath that you cannot quite access, one that informs the work and gives it a multilayered intelligence.

This quality of playful hauntedness is key to interpreting much of the GALA Committee’s work. Safety Sheets is funny because the idea of this lothario doctor making his bed with condom bed linens is funny, but it is one of many pieces that reference the AIDS crisis. Viruses pop up everywhere in In the Name of the Place. One poster, based on the work of Barbara Kruger, prints the slogan “Think of the Reruns” over an ominous image of a virus. In one episode, a blind date flees Sydney’s apartment nude, covering himself with a GALA pillow sporting an image of the AIDS virus. A sculpture called TV Phage is a straightforward depiction of a virus, recognizable by anyone who has taken high school biology, made out of a cathode-ray tube and television antennae.

GALA Committee and CBS Home Entertainment

Chin conceived of the GALA Committee functioning like a virus, using the RNA of its artwork to infect the host of Melrose Place and, from there, spreading the art far and wide. But the viral conceptual framework also ties into the AIDS crisis, which was in the midst of one of its most brutal years when In the Name of the Place launched. Television and the AIDS crisis had a complicated relationship. A year before the formation of the GALA Committee, HBO had aired the star-studded ensemble drama And the Band Played On, based on Randy Shilts’ book of the same name, which documented the first few years of the crisis and the quest to find out what caused the disease. But discussions of safe sex were largely verboten within hits like Melrose Place, and outside of a Very Special Episode or two, the AIDS crisis often went unmentioned on network TV. The crisis was the dead movie star inside the painting of the house. The GALA Committee was attempting to open the door to that house, just a little bit, so viewers could see what was inside.

Images of violence proliferate as well: pens made out of bullets; a coat lined with the image of the burning Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas; and a mail carrier’s bag with an AK-47 clip sewn into it. This is art that uses humor where normally one would expect rage, like a stand-up routine delivered at a protest rally. But because it is operating like a virus, there is also a curious restraint, a mysteriousness. What does a pen shaped like a bullet mean? Or a quilt with RU-486’s chemical formula printed on it? The work requires knowledge of its original context to gain its full meaning. It is only through knowing that the art expresses thematic and political content that network television would rather leave offscreen that we actually begin to truly see the art in full.

And yet, within its original context, hardly anyone saw it at all.

In March 1997, the GALA Committee finally got the chance to reveal to the art world what it had been up to. Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art opened an enormous survey of bleeding-edge visual and performance art called Uncommon Sense, intended to interrogate the role of the museum in the art experience. Amid nude-drawing classes hosted by Karen Finley and a rodeo featuring an actual horse, GALA installed a collection of works from In the Name of the Place, including a full-scale replica of Shooters bar, in which patrons could buy a drink.

Before the show opened at MOCA, the Gala Committee and the staff at Melrose threw one last hurrah, filming a pivotal scene within the exhibit of objects that had previously appeared on the television show. “There was a fake director,” MOCA curator Julie Lazar recalled. “There was a fake museum communications director. There was art that wasn’t art, but it was art.” The scene even featured Heather Locklear, the actor whose blond hair had inspired Mel Chin in the first place, walking through the gallery, talking about the artwork. You can see GALA’s TV Phage lurking behind her.

Lazar loved having Melrose film at MOCA. It paralleled, she thought, everything she was trying to do with Uncommon Sense. “Was the work that was on the screen and set behind the actors art?” she asked. “When was it art? Was it when it was on the television show, or was it when they came to the gallery and it was hanging behind them?” The pieces made for Melrose were both artwork and props, serving multiple functions at once, but they also transformed the show’s purpose. Now it was not only a soap opera—a genre named for its ability to sell products—but a permanent record of the GALA Committee’s work, an installation space for the collective’s art.

But when Uncommon Sense opened, the reviews for the survey were scathing. In the New York Times, influential critic Roberta Smith wrote, “It’s sad when artists and curators don’t like museums or art,” and she only grew more negative from there. Though she appreciated the GALA Committee’s cleverness, she dismissed its work as having “the raw, discombobulated feeling of a group show of young, undeveloped artists.”

Another person who was not amused was Aaron Spelling. He had finally learned about the two-year political prank happening on the set of one of his most successful shows from a Talk of the Town piece in the New Yorker timed to the art show. Early one morning, Frank South was summoned to Spelling’s office. According to South, after he walked in across “an acre of shag carpeting,” Spelling asked him how long he had known about the GALA Committee’s work.

“Well,” South said. “You know, a year and a half, two years and a half.”

“So when were you going to tell me?” Spelling asked.

“Oh, Aaron,” South said. “I figured as late as possible.”

One line in Smith’s review has really stuck with Tom Finkelpearl, the co-curator of Uncommon Sense: “It is impossible not to feel that the real action is taking place elsewhere, that the most fun was or will be had by those directly involved.” When I spoke to him recently, he agreed: “It is also sort of true.” The GALA Committee was having a profound experience of making art and distributing it in new, innovative, and subversive ways, but that experience didn’t necessarily translate to the audience in the museum.

It also didn’t necessarily work for the audience sitting at home watching television. I first read about In the Name of the Place in On Edge, a collection of essays by C. Carr, a brilliant journalist who covered experimental art for years in the pages of the Village Voice. I loved the story. I mean, sheets with condoms on them on network television? During the AIDS crisis? That’s incredible.

The GALA Committee/CBS Home Entertainment

But I have yet to find a single viewer of Melrose Place who has any memory of seeing any of the artworks while watching the show. Much of the work appears too briefly, or in the dark background of a standard-definition broadcast. It’s hard to pay attention to the set when characters are busy stealing one another’s babies or faking their deaths. The virus of the GALA Committee did take hold of its host, Melrose Place, but it never really spread to the next target, the viewers. None of these artworks, clever as they were, went “viral” in the modern sense.

How does Chin feel about that? Was it frustrating? Or was that simply the risk they ran keeping the project so secret? “Everything was new,” he told me. “No one had ever created public artwork on a TV show before. It’s totally experimental. So, yeah, I understood that might happen.” But then he returned to his initial inspiration: “It’s about patience. It’s like a virus entering your world.”

The virus of In the Name of the Place has proved durable—it was even remounted by the energy drink Red Bull in a gallery in 2016, and an independent publisher has printed the exhibition catalog as an art book—but it has never been quite contagious enough to become an epidemic. If anything, the project was about a decade ahead of its time. In the Name of the Place anticipates the Easter egg but existed prior to the kinds of fandom communities that would pore over footage of their favorite shows frame by frame to find those surprises and post them on the internet. It also existed before HDTV, or widespread recapping sites, or even DVD players. These days, people record for their YouTube channels nine-hour explanations of how Game of Thrones explains the world. We are all searchers of hidden messages, treating each episode of our favorite show as a series of clues to be decoded.

It is very seldom that we get the opportunity to see art in its original context. When we go to a museum, we are viewing work that was originally intended for religious spaces, or Parisian salons in the 19th century, or the Leo Castelli Gallery at 4 E. 77th St. in Manhattan. Yet you can experience In the Name of the Place in its original context right now: Just stream an episode of Melrose Place from the show’s fourth or fifth season. Knowing what to look for transforms both the art project and the TV show that incubated it. Instead of a series of random curios, what emerges is a surreal embedding of the subtext of 1990s American life into the urtext of 1990s America: the American unspoken, slipped into the biggest, brightest, blondest version of America there was.

Soap operas have always been vehicles for our anxieties about marriage, domestic life, the workplace, and whether we could trust—or truly know—one another. In Melrose Place, those anxieties manifested in delicious plot twists, but the origins of those anxieties—the tyranny of heteronormativity, the AIDS crisis, the legacy of slavery—also popped up, subliminally but repeatedly, in a hundred or so mysterious, often hilarious objects. It’s as if the characters are dreaming, as if all of us are dreaming, and our subconscious keeps trying to show us something: something we could see, if only we could pay close enough attention.