One of my favorite plays of the 1980s was the Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Heidi Chronicles,” by Wendy Wasserstein. I loved following the adventures of the protagonist, Heidi Holland, as she evolved from 1960s idealist to 1980s art historian.

In the play, Heidi specializes in studying and lecturing about women artists, and protests the lack of female representation in major art museums.

Back then Heidi, and Wasserstein, inspired me to learn a bit more about women artists and works I wasn’t familiar with, such as feminist multimedia pioneer Judy Chicago and her “The Dinner Party” installation of a triangular table with place settings designated for 39 important women in history.

I thought about Heidi Holland recently when I started reading a new book, “The Story of Art Without Men,” by British art historian Katy Hessel.

Gallery in NATIONAL MUSEUM OF WOMEN IN THE ARTS in Washington, DC

Hessel was inspired to write about women artists from the 16th century to the present after visiting a large “art fair” and finding it devoid of works by women.

In the book, Hessel cites a 2019 study showing that in the collections of 18 major U.S. art museums, 87% of the works were by men, and 85% by white artists. Just 1% of London’s National Gallery’s works are by women, she writes, and 30% of the British citizens she surveyed couldn’t come up with the names of more than three women artists.

I know local women artists who exhibit their work in Lancaster County galleries. Over time, I’ve gained deeper understanding of some artists, like Berthe Morisot, Georgia O’Keeffe and former Lancaster resident Mary Cassatt, because of their popularity, and others through movies — Lee Krasner from a film about her husband, Jackson Pollock, and painters Frida Kahlo, Artemisia Gentileschi and sculptor Camille Claudel from the biopics made about their lives and work.

Artist: Anne Seymour Damer (English, 1748 – 1828) Shock Dog c.1782 Marble Overall: 13 1/8 × 14 15/16 × 12 5/8 in. (33.3 × 37.9 × 32.1 cm.), 75 lbs Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Barbara Walters Gift, in honor of Cha Cha, 2014 (2014.568) RW221

I’m a fan of works by Henri Matisse, Vincent van Gogh, Marc Chagall, Emile Nolde, Odilon Redon, Constantin Brancusi and lots of others. But I also recognize that, going back centuries, there are works of art and craft by women that are every bit as fabulous as the works by the male artists I was raised on in school, books and museums.

So, like Wasserstein, Hessel — who also has a podcast about women artists — has sent me on a bit of a quest, to, yet again, learn more about work by women artists, both contemporary and in centuries past.

To that end, I recently sought out two regional spaces where I could see lots of art by women. I attended a press preview for the reopening of the spectacular, 36-year-old National Museum for Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., after its two-year, $70 million renovation. And I toured a new exhibit called “Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800,” at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

The lobby of the newly reopened National Museum for Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C.

A national museum

“One of the things that we have been doing here for almost the past 40 years is really rewriting art history,” Katie Wat, the chief curator at the National Museum for Women in the Arts told me at the press preview. “When we first opened in the 1980s, we were trying to recover women who had been written out of history … .” The museum was the first in the world solely dedicated to championing art by women.

“I’m very cheered by the progress that’s been made, particularly over the last couple of years,” Wat said. “But I feel like it’s early days. I don’t know if this is a sea change yet or not. … And I just feel like we can’t take our foot off the gas pedal until we all feel certain that we’ve actually achieved equity and representation” for women artists.

Hung Liu, Summer with Cynical Fish, 2014; Oil on canvas, 60 x 72 in.; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of the Artist and Turner Carroll Gallery in honor of Nancy Livingston

Standing in the museum’s grand marble lobby, with its chandeliers and sweeping staircases, it was interesting to remember that the building was once a Masonic temple that women were forbidden to enter.

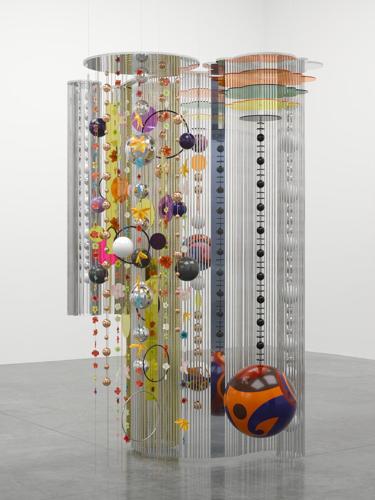

With expanded gallery space, the renovated museum allows large-scale pieces by women to stand tall and take up as much room as they need —without having to ask permission.

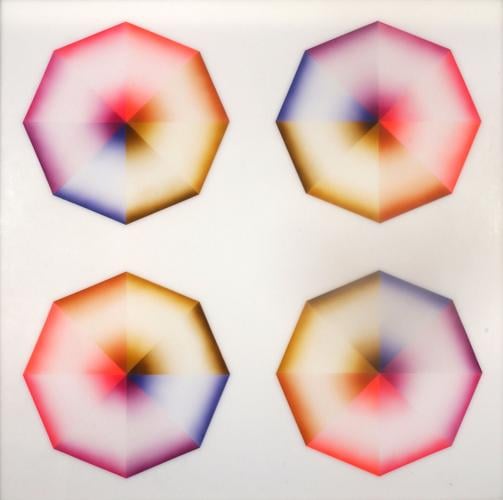

Joana Vasconcelos, Rubra, 2016; Murano glass, hand-crocheted wool, ornaments, LED lighting, polyester, and iron, 69 1/4 x 43 in. diameter; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Christine Suppes; © Atelier Joana Vasconcelos; Photo by Francesco Allegretto Photographer: Francesco Allegretto

A new exhibit titled “The Sky’s the Limit” highlights just such large works — colorful bronze bells, hanging enamel sculptures filled with flowers and Joana Vasconcelos’ massive, bright-red glass-and-wool chandelier that hangs over the entrance to the lobby.

Since 2017, the works in the museum have been organized thematically rather than chronologically, Wat said, so a 16th-century Italian noblewoman’s portrait by Lavinia Fontana hangs near a 2022 Alison Saar sculpture of a woman wearing a belt of iron skillets and brandishing one as a potential weapon — based on the Amazonian queen Hippolyta.

One of my favorite pieces in the museum is an undated photo of writer Ethel Watts Mumford, shot by Jessie Tarbox Beals, the first published woman photojournalist in the United States.

I was drawn to a photo print called “Purple Atmospheres” and — hello, Judy! — found it’s an image of one of Judy Chicago’s early experiments in manipulating large amounts of colored smoke across an outdoor landscape.

“Untitled” (Smithport, NJ),” by Lancaster native Victoria Sambunaris, hangs in the National Museum for Women in the arts.

Lancaster native Victoria Sambunaris, a photographer of the American landscape who exhibited her works at the Demuth Museum in 2012, is represented with a large photo of colorful, stacked shipping containers in Elizabethport, New Jersey.

If you visit the museum, don’t miss four short films, shown in a small screening room off the main lobby, that profile four contemporary women artists and offer a deeper understanding of their creative processes.

Artist: Marie Victoire Lemoine (French, 1754 – 1820) Youth in an Embroidered Vest 1785 Oil on canvas From the exhibit “Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800” at the Baltimore Museum of Art Overall: 25 5/8 × 21 1/2 in. (65.1 × 54.6 cm.) Framed: 33 1/2 × 28 3/4 × 3 in. (85.1 × 73 × 7.6 cm.) Purchased with funds from the Cummer Council, Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, Jacksonville, Florida, AP.1994.3.1 RW06

Art from centuries past

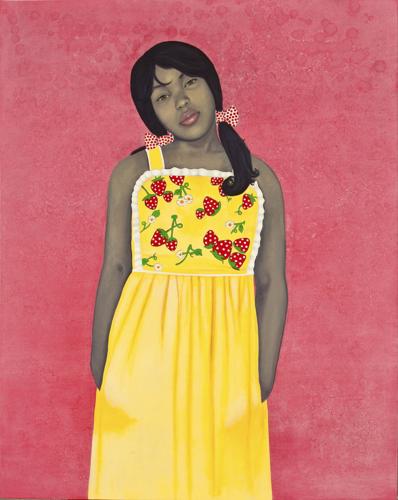

In the Baltimore exhibit, I wandered through galleries filled with four centuries’ worth of works by women artists, many of whose names are either obscure or have been lost to history — the kind Hessel seeks to elevate in her book.

The mediums in which these women worked include illuminated manuscripts by nuns, massive allegorical tapestries, ornate lace work, decorated tea settings in porcelain and silver, wooden furniture, ceramics, an embroidered gown, drawings, paintings and sculptures.

The women painted religious figures and birds, tigers and planets, flowers and portraits of women at their writing desks.

04. The Entrepreneurial Spirit Artist: Marie-Victoire Jaquotot (French, 1772 – 1855) Tea Service of Famous Women (Cabaret des femmes celèbres) 1811-12 Hard-paste porcelain From the exhibit “Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800” Overall (teapot with Anne and Christina): 8 1/16 × 8 1/4 × 4 7/8 in. (20.5 × 21 × 12.4 cm.)

I learned about Josefa Ayala, a 17th-century Portuguese painter, who interpreted Jesus as a child pilgrim, with a fancy cape and a plumed hat, and also painted still-lifes filled with fruits and vegetables.

Seventeenth-century Dutch painter Judith Leyster looks out at us from her self-portrait, with happiness and confidence as she works at her easel.

My favorite section of the exhibit celebrates women who painted birds, flowers, plants and other subjects from nature, and speculated at scientific truths through their art.

Seventeenth-century German artist Mara Clara Eimmart created tempera works on paper that explored aspects of the planets and the moon.

Artist: Anne Seymour Damer (English, 1748 – 1828) Shock Dog c.1782 Marble Overall: 13 1/8 × 14 15/16 × 12 5/8 in. (33.3 × 37.9 × 32.1 cm.), 75 lbs Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Barbara Walters Gift, in honor of Cha Cha, 2014 (2014.568) RW221

These museum visits have convinced me to make a more concerted effort to explore the work and the biographies of many more women artists.

As I chatted at the National Museum for Women in the Arts with a correspondent for a New York arts website, I asked her if there’s an exhibit I shouldn’t miss the next time I have time for a museum while in New York. She thought a minute.

“I think you’d really like the Judy Chicago exhibit [“Herstory”] at the New Museum,” she said.

I had to smile. Heidi Holland would be proud.

Mary Ellen Wright is deputy team leader for Life & Culture for LNP | LancasterOnline. “Unscripted” is a weekly entertainment column produced by a rotating team of writers.

![6 books, events, movies to check out before Halloween this year [Unscripted column]](https://bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/lancasteronline.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/3/33/33377e48-71a9-11ee-8018-8fa227fc2051/6536770948339.image.jpg?resize=150%2C200)