Since the first cassette tape was invented 60 years ago on Thursday, nowhere has its impact been more tangible than across the Middle East.

Invented by Lou Ottens, a Dutch engineer who worked for Philips, the two-spool cassette tape debuted in 1963 at an exhibition in Berlin. Selling over 100 billion cassette tapes worldwide, people no longer had to buy records or listen to content marred by censorship or gatekeepers of record companies and radio stations. The cheap, pocket-sized device revolutionised access, giving power to the people.

In the Arab world, the cassette tape functioned as something much greater than a medium to listen to music. It metamorphosed into a cultural, political and even a religious vehicle, immortalising music, spreading knowledge and calls for revolution, and connecting families and loved ones separated by migration and civil war with cassette letters that some treasure long after the cassette’s decline.

In Egypt, the proliferation of cassette technology was sparked by transnational travel during the oil boom, when migration became a popular practice and the cassette became a symbol of upward economic mobility.

“The dawn of cassette culture more broadly coincides with the beginning of mass consumption in Egypt, against not only the backdrop of the oil boom, but also the ‘Infitah’, the economic opening [of 1971-1980],” says Andrew Simon, the author of Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt.

Stay informed with MEE’s newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis,

starting with Turkey Unpacked

“More Egyptians were on the move than ever before, and one of the objects they often bought from abroad were cassette players, along with electric fans.”

In 1970s Egypt, radio was under state control from 1934. Much to the dismay of screening committees responsible for filtering content so that everything broadcast complied with artistic, political and religious norms, “all of a sudden, anyone could record their voice and reach a mass audience”, Simon says, adding that a lot of cassette technology was smuggled across Egypt’s national borders, airports and its docks in the coastal city of Alexandria.

“Whether among elites or among the working class, cassettes are really a technology that transcends class,” says Simon.

As the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait unfolded in 1990 – a move triggered by land and oil disputes – the subsequent Gulf War triggered millions of migrant workers, many of them unskilled labourers, to return home. Taking with them only essentials they could carry in their hands, some Egyptian workers took cassette players with them.

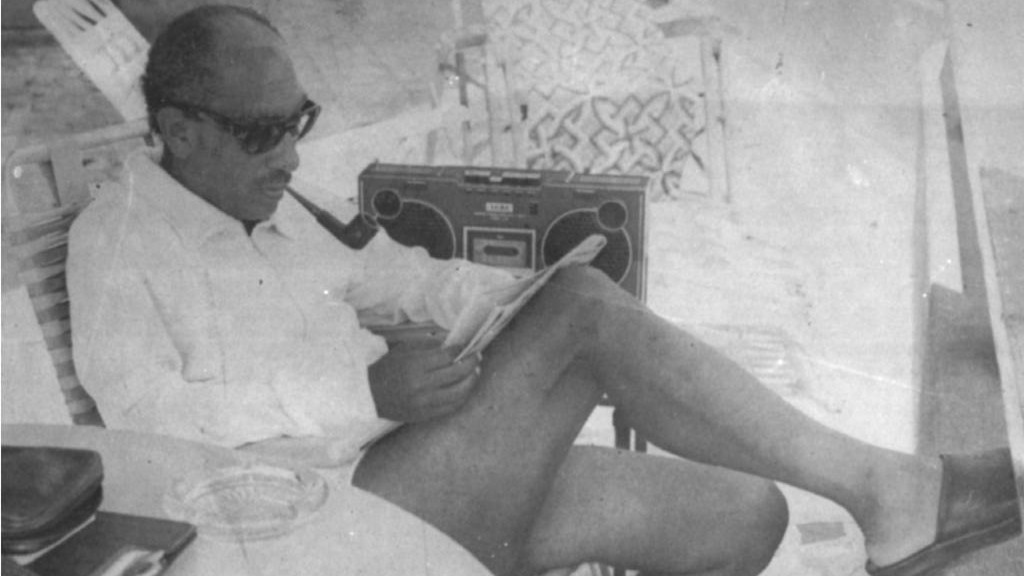

The cassette player, which epitomised Egypt’s 1970s “economy of desire” according to Simon, even found its way into a photoshoot of Anwar Sadat, Egypt’s president who was assassinated at a televised military parade in 1981.

In a photograph published in the Egyptian newspaper, Akbhar al-Yawm, Sadat can be seen reclining on a chair wearing sunglasses, listening to a cassette player.

“Although Sadat was an elite in Egyptian society, being a head of state, the whole purpose of the photoshoot, this ‘day in the life of Anwar Sadat’, was to depict him as an ordinary Egyptian,” Simon says.

A vehicle for cultural innovation for shaabi singers

The inception of the cassette empowered the everyday Egyptian to contribute to the creation and circulation of culture in Egypt.

Shaabi music, a style of working-class music sung in colloquial Arabic, sometimes played at weddings, street corners or vehicles, suddenly found a foothold in cassette tapes that escaped the asphyxiation of Egypt’s state-controlled radio stations who refused to platform music it perceived as too “vulgar”.

Among the shaabi musicians who ascended with the inception of the cassette tape was the pioneer Ahmad Adawiya, whose 1973 debut tape al-Sah al-Dah Ambu sold a million copies.

At the same time, propaganda vilifying shaabi singers singing to the everyday experiences of Egyptians, began to circulate in the popular Egyptian press, according to Simon.

They ended up at the very centre of those commentaries, as ushering in “‘the downfall of music, the death of public taste, the end of high culture'”, Simon says. “From the perspective of cultural critics, ordinary people in the 1970s and 1980s had no business making Egyptian culture. They should be cultural consumers, not cultural producers.”

The vilification of shaabi singers in the 1970s is reminiscent of recent criticism of mahraganat, the popular, electronic folk music that has amassed millions of views on YouTube and SoundCloud. The genre, which initially emerged from some of Egypt’s most impoverished districts, has been dubbed as “immoral”. One maghranat star on TikTok was even sentenced last year to prison on the grounds of “human trafficking” in Egypt.

The digitisation of cassette recordings

In recent years, the cassette has enjoyed a renewed popularity among younger generations discovering them for the first time.

As civil war, occupation and changing technologies continue to leave their mark in some parts of the Middle East, the cassette has also become a rich source of nostalgia and history for Arabs and those in the diaspora who have digitised musical repertoires and artwork that would otherwise have been forgotten.

One project preserving a fragment of the cassette era of the Arab world is Syrian Cassette Archives, a collection of recordings spanning the 1970s to the 2000s that also includes Iraqi cassettes and music.

Created by producer and archivist Mark Gergis who began the archive from hundreds of cassette tapes he purchased in music shops and kiosks across Syria before the civil war, the music includes a variation of regional dabke, shaabi folk-pop music, classical, live concert, wedding and party, studio albums, and even children’s music.

Majazz Project, a Palestinian-led record label and research platform founded by Momin Swaitat, is another archive of rare tapes and vinyl from Palestine.

With much of its content mainly from the 1960s to the 1990s acquired from a former record label in Jenin, the audio is a mixture of revolutionary tracks, liberation songs from the Intifadas, recordings from Bedouin weddings, and even synth-heavy 80s funk and jazz.

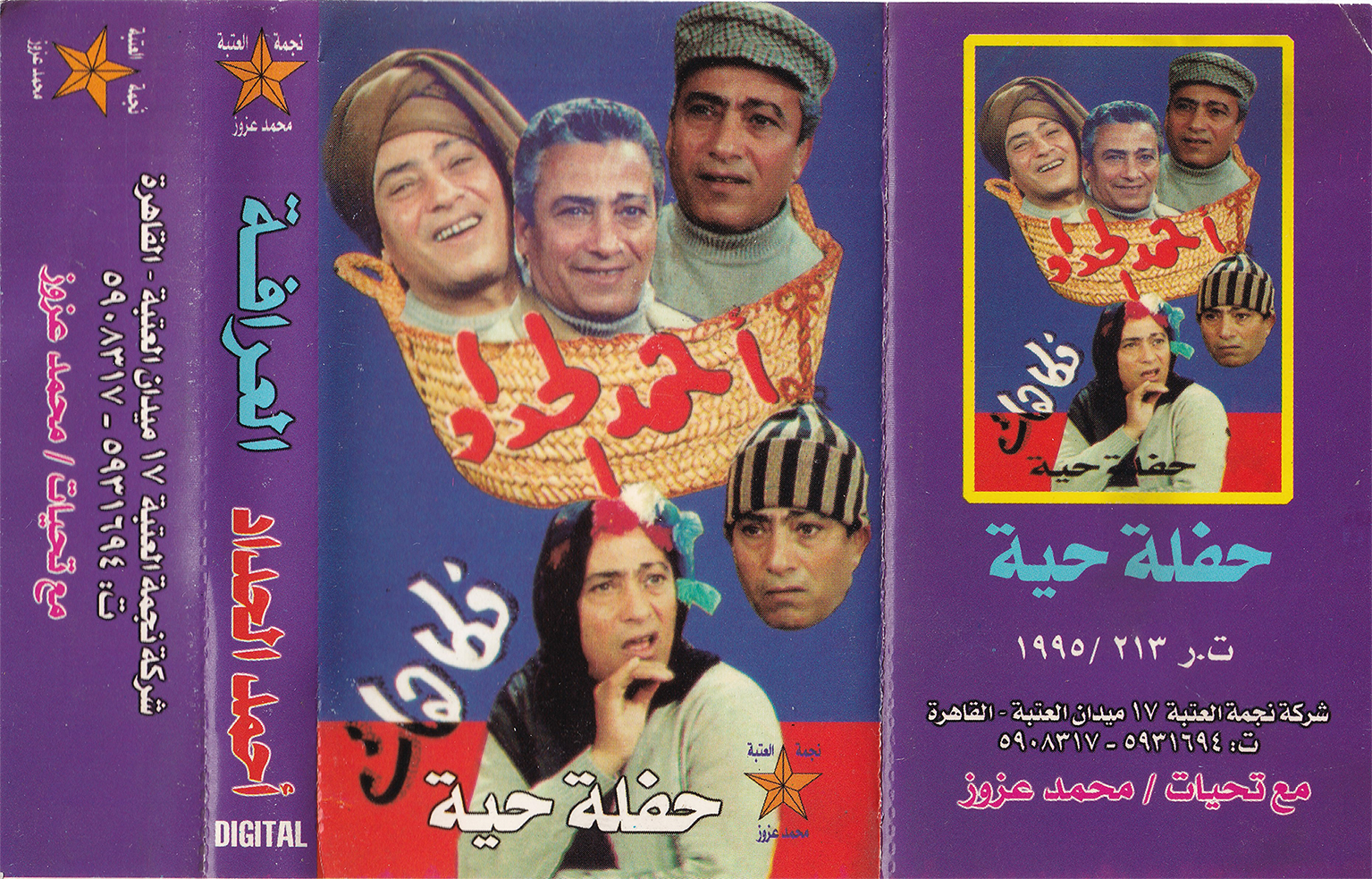

Amr Hamid, an Egyptian visual artist and graphic designer based in Sweden, is the founder of Egyptian Cassettes Archives. With a collection that has ballooned into nearly 7,000 cassettes, all of them music from across Egypt’s regions and genres, and even personal recordings, Hamid’s interest stemmed from a box of cassettes he stumbled across at home.

“This was the only medium we had at the time in the beginning of the 90s. It was all about music,” Hamid says of growing up listening to cassettes.

“But when I grew after some years of my fine art college, I started to look back into my stuff, and I found out that I had a box filled with cassettes. I got really interested immediately about the visuals. ‘Who designed these beautiful designs?’ It was really hard to find answers, so that’s the beginning of the project.”

Using Instagram to share cassette tape covers, Hamid has managed to identify some of the artists, and he has nurtured an online following of fellow enthusiasts. Some of the covers feature Mahmoud El-Khatib or “Bibo”, the former legendary football player for Al-Ahly football club (and now its president). Another features the Egyptian actor and singer of shaabi music Ahmed Adaweyah, standing in front of the pyramids of Giza.

The cassette tape also became a significant vehicle for politics in the region.

In the pre-internet days of 1978, Ayatollah Khomeini led the Iranian revolution in exile using cassettes on which he recorded speeches from Neauphle-Le-Chateau in a sedate village west of Paris. The tapes were sold in Europe and delivered to Iran before his return in February 1979.

Following Israel’s withdrawal from southern Lebanon in 2000, traditional Hezbollah songs and speeches by the group’s most dominant leader, Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah – a resistance figure accredited with driving Israel out of southern Lebanon after 20 years of occupation, but equally a controversial figure seen to be responsible for exacerbating conflict in Lebanon – were sold widely.

With telephones and cassette tape recorders, new communication media led to a form of “religious revivalism” in Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East, according to US academic Eric Schewe.

Cassette Letters

Sixty years after the cassette tape was invented, perhaps its legacy will be remembered most in the poignant emotional importance it carries now.

Long before voice notes on WhatsApp, for many Arab families migrating far away from home, cassette tapes acquired sentimental value as a mode of long-distance communication.

Rania Hafez was 11 when the Lebanese civil war broke out in 1975, a war that left over 120,000 dead and forced nearly a million people to flee the country until it ended 15 years later.

The 59-year-old Lebanese professor in education and society at the University of Greenwich who now lives in London, recalls leaving her boarding school in Beirut for Abu Dhabi, to join her father who was working in construction.

For two years, they could not see their family in Lebanon, and telephone communication, now globally ubiquitous, was not easy at the time. She vividly remembers cringing at the sound of her own voice, in a cassette letter monologue her family sent to her grandmother, aunt and uncles who were still in Lebanon.

“They were not music tapes, it was just us talking,” Hafez says. “We would just say things like, ‘We miss you. This is what we’re doing here. How are you doing? Let us hear back from you’.”

With postal services not functioning because of the war, Hafez’s family sent their cassette letters with anyone travelling to Lebanon.

“My grandmother was probably a bit reticent to say much. I remember maybe a few words from her, as it was all too much new technology for her. But my aunt would send things back,” Hafez recalls.