“The sooner that we get to the moon, the sooner we get American astronauts to Mars,” NASA recently wrote. “Mars remains the ultimate destination of NASA’s human exploration program,” said NASA Administrator, Senator Bill Nelson to Congress in 2020.

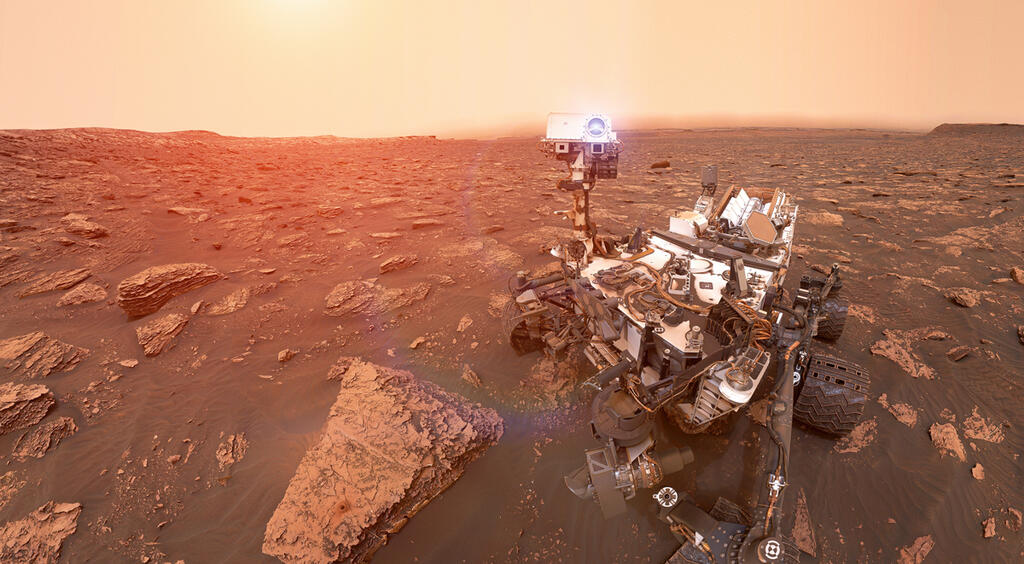

There are many reasons to explore Mars, from learning more about the origins of life due to Mars’ relatively similar environmental conditions to Earth, to the development of new technologies and building infrastructure for space tourism and resource extraction. In 1976, NASA successfully landed the Mars Rover, which provided extraordinary images of the planet and its barren surface, as well as soil samples. However, since then, the dream of completing a manned mission to Mars has stagnated. There also hasn’t been a manned mission to the moon since Apollo 17 in 1972. Reducing the presence on the moon allows NASA to focus on training missions and refining technologies relevant to Mars.

2 View gallery

The Mars Rover.

(Credit: Shutterstock)

Fifty years have passed since the last successful probe landing on Mars in 1976, and only a handful of additional missions aimed at Mars have been successful. Russia, for example, has attempted nearly 20 Mars missions over the years, including satellites, probes, and spacecraft, and almost all of them have failed. However, in the last decade, something changed, and various countries and private actors have once again started talking about manned missions to Mars. In recent years, successful missions have been sent to Mars by the United States, India, China, and even the United Arab Emirates, which successfully launched a probe on a Mitsubishi rocket.

Mars is the planet most similar to Earth and is also closest in proximity, with a distance of “only” 56 million kilometers.

Each country has a different approach to reaching Mars. In India, the funding is public, the project is largely civilian, transparent, and involves some commercial collaborations. The Chinese project is government-funded and military-led, resulting in a relatively secretive and heavily funded initiative. In Europe, there is collaboration between the European Space Agency and Russian space agency Roscosmos via the ExoMars programme, which included a failed attempt to land a rover on Mars in 2018, with another rover mission expected to reach Mars in the near future.

In the United States, the project was once a source of national pride, receiving about 5% of the federal budget in the 1970s. Today, however, the project relies significantly on commercial partnerships, with government funding comprising only about 0.5% of the federal budget. In addition to various government agencies, private initiatives have also emerged, such as the private consortium led by Virgin Orbit’s Richard Branson, designed to send satellites to Mars, although the company has since declared bankruptcy.

For China and the United States, the race to Mars serves as a geopolitical tool, even though there have been periods when cooperation in space was considered. This approach, “for the benefit of all humankind,” was enshrined in the National Aeronautics and Space Act, and is engraved on lunar landing vehicles. Even before that, it was codified in the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, with 113 signatories, including the United States, Russia, and China, which states that “The exploration and use of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind. Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall be free for exploration and use by all States without discrimination of any kind.”

In 2011, the United States decided to distance itself from this universalism through a law called the Wolf Amendment, which prohibits NASA from cooperating with China on space exploration. According to the amendment, NASA, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), and the National Space Council are not allowed to collaborate, host, or coordinate with China or any Chinese-owned entity, and the FBI must certify in advance that there is no risk of data sharing, and that none of the involved Chinese officials are directly involved in human rights violations.

China’s isolation from US-led international missions has not deterred it; on the contrary, it has pushed China to accelerate development of its own capabilities. Since China cannot participate in the International Space Station (ISS), it is developing its own modular space station. China has already launched its space stations, Tiangong-1 and Tiangong-2, into Earth’s orbit for manned missions.

In the meantime, China has set a target of landing humans on Mars by 2033, in addition to several long-term plans, including missions planned for 2035, 2037, and 2041. These plans were detailed to the public for the first time in 2021 after China successfully landed its first Mars rover, Tianwen-1, China’s first successful Mars mission following the failure of its previous mission, Yinghuo-1, in 2011. China has also announced plans to send additional rovers to explore potential Mars base sites and build various systems for resource extraction, including water, oxygen, and electricity production. China has been actively seeking to attract international cooperation, including offering frequent launches at attractive prices.

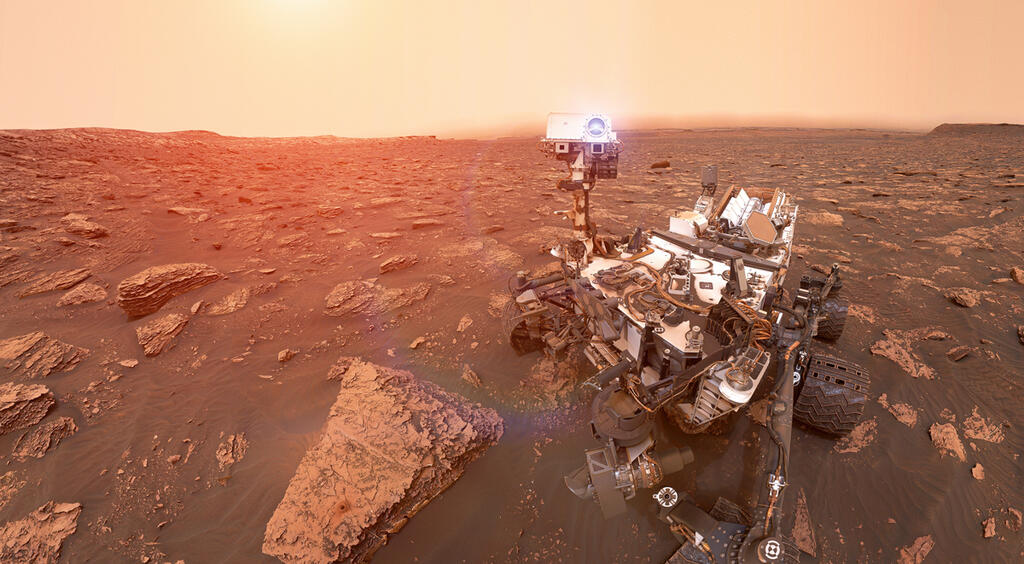

2 View gallery

A Chinese launch to Mars.

(Credit: AFP)

After successful Mars missions last year, India and the United States are catching up with plans of their own. “Our strategic competitors, including China, invest aggressively in a wide range of space technologies, including nuclear power and propulsion to fulfill their aspirations for a sustained human presence on the moon, as well as missions to Mars and outer space,” said a senior NASA adviser to a congressional science committee. She noted that “it is difficult to obtain precise information about China’s research plans” but that China has created a “very aggressive space development program.”

Last year, China also announced plans to become the first country to collect samples from Mars and send them back to Earth. Zhang Rongquiao, the chief designer of Tianwen-1, China’s first mission to Mars, presented plans for two Mars sample return missions set to launch in late 2028 and return samples to Earth in July 2031. “For the complex multi-launch mission, the architecture will be simpler compared to NASA’s project,” it said. This project involves sending samples collected by the Mars Ascent Vehicle, which is supposed to take place after 2031.

In the United States, these developments raise concerns that the race to Mars is not purely driven by scientific curiosity but is also part of the global power struggle during a tumultuous political period. Investment in outer space and Mars projects can help the United States maintain its global technological advantage. With this in mind, the U.S. launched the Artemis program to establish a space station orbiting the moon, called the Lunar Gateway, and is seeking to land a manned mission on the Moon for the first time since Apollo 17 in 1972. The U.S. negotiated with seven countries (Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the UAE, and the UK) and established the “Artemis Accords,” allowing specific countries and private companies to create exclusive zones on the Moon, build settlements, engage in space tourism, or engage in mining activities in those areas.

The U.S.’s position as the dominant power in space has been bolstered by the significant involvement of private American entrepreneurs in establishing space companies. Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, established Blue Origin, Elon Musk founded SpaceX, Paul Allen, the co-founder of Microsoft, funded the SpaceShipOne project, and Larry Page and Eric Schmidt of Google supported asteroid mining company Planetary Resources. Their investments and support have significantly contributed to the development of the current space race. In 2015, then-President Barack Obama furthered this by signing the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, granting American businesses the right to exploit space resources. President Donald Trump expanded on this in 2020 with an executive order allowing for commercial development of space resources, explicitly rejecting the idea that space is the common heritage of all humanity.

Within this space race, two major private space barons emerged: Bezos and Musk, each with very different strategies. Musk has been talking about the journey to Mars for years and sees it as the key to saving humanity from an inevitable catastrophe. He founded SpaceX in 2002 with the stated goal of making humans a “multiplanetary species” that can establish a “self-sustaining city” on Mars. According to Musk, the first settlers will live in underground caves and rely on cargo shipments to Mars every 26 months. Ultimately, they will be able to live on the surface after terraforming Mars as much as possible. “It’s a little cold,” the company’s website says about Mars, where the average temperature is minus 63 degrees Celsius, “but we can warm it up.” How? By dropping atomic bombs. You can even buy a T-shirt with the slogan “Nuke Mars” on SpaceX’s website for $30. Most scientists consider this plan to be ridiculous.

Musk had promised manned missions to Mars by 2020, then moved the date to 2025, and later to 2030. Now, he aims to bring up to a million people to Mars by 2050. The price for the initial tickets is estimated to be around $10 billion, but with rocket reusability and efficiency improvements, he believes the cost of a ticket could drop to as low as $200,000. At this price point, he envisions that “almost anyone” will be able to go to Mars. From his perspective, settling on Mars is inevitable, the only way to save humanity from the increasingly inhospitable conditions on Earth. Earth must be left behind, and we must start anew on Mars, where we can build everything from scratch.

Bezos’ approach is the opposite. He believes that there is no escape from Earth to Mars; instead, we should preserve and use Earth. “Believe me,” he once said, “Earth is the best planet.” For those who are contemplating moving to Mars, he suggested that they “first go live in Antarctica for three years and then tell me how you feel because Antarctica is paradise compared to Mars.” For Bezos, Earth must be preserved, and space should be used for heavy industry exports and the establishment of settlements to provide Earth with the required respite for its recovery.